This assertion must also have been shared by Phra Kru Ba Neua Chai, a Thai boxing champion who, in 1980, renounced everything, became an ordained monk and founded the Golden Horse Monastery, nestled in the fog-shrouded hills north of Chiang Rai, near the Thai-Myanmar border.

He has transformed what was once a semi-uninhabited forest into an area with paddocks and chicken coops for dozens of Thai horses and magnificent fighting cocks. The monastery has also become home to numerous children from different tribes in the neighbouring hills. They have been orphaned, abandoned or homeless because of the ruthless drug guerrillas who smuggle heroin, opium and methamphetamine into the area, known to the world as the Golden Triangle. In the Golden Horse Monastery, these boys are ordained as novice monks and learn to read and write. The abbot also teaches him Buddhist scriptures, horse riding and Muay Thai. This is the ‘noble’ part of the project. Alongside is another that, if not less noble, certainly raises some doubts. At least judging by some ‘details’.

The weekly ceremony of prayer and reception of devotees starts early. It is a Thursday morning in the hot month of June. The sound of a gong announces the opening of the celebration. The few worshippers who had come gathered around a statue of Buddha in the corner of a small square. Chairs are placed around the perimeter. The faithful sit down and in silent recollection begin their prayers. More ringing of gongs and bells struck by staff. They are no monks. They are young people from the surrounding villages or guests who help the monks. In the distance, hoofbeats signal the arrival of the clerics.

The blessing ceremony

On horseback, covered in orange robes, a squad of clergy climbs a slope to the left of the small square. Leading them is the highest-ranking, purple-robed deputy of the monastery’s founder. At the pass, the novices’ steeds stop in single file while the senior monk approaches the faithful. A curt nod and a smile. A microphone broadcasts the prayer litanies. The whole thing lasts no more than half an hour.

As it unfolded, the ceremony included the sprinkling of water, which the pilgrims had previously purchased from the monks themselves, as a sign of goodwill and blessing, on the earth and concrete floor. The officiant does not pour the liquid on the ground like the devotees but collects it inside a bucket. The rite ends with what could be read as a general blessing. After the service is over, the other monks are also brought to the high ground. Pilgrims get up and walk towards them with various gifts in their hands. It is the breaking point.

The breaking point

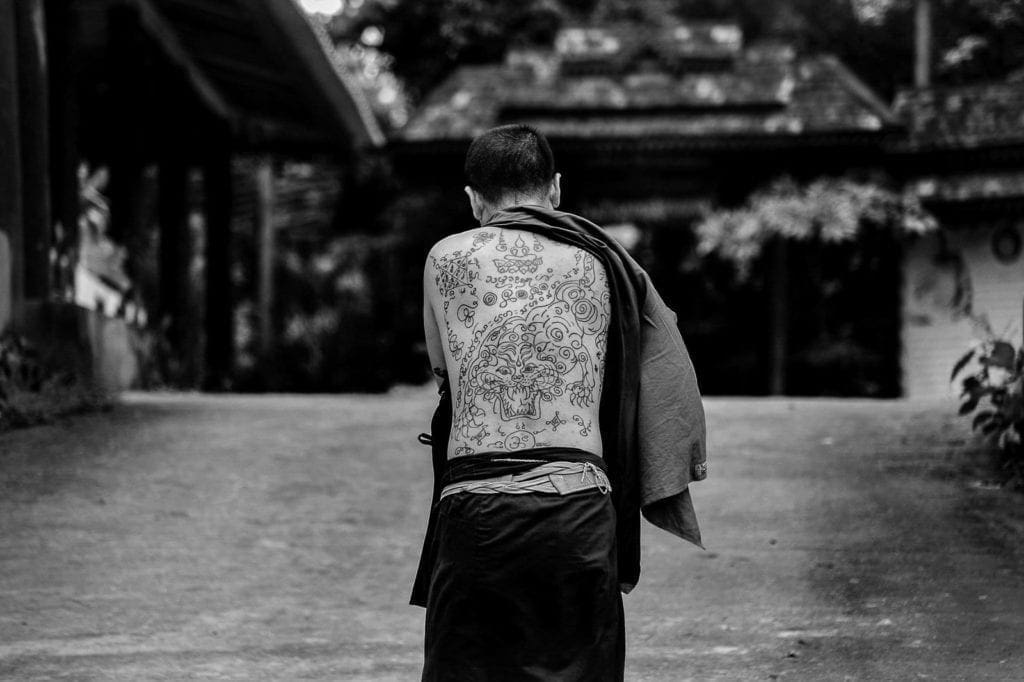

At this instant, the occidental mentality begins to notice flaws or inconsistencies that it cannot explain due to its limitations. The faithful present the monks, still on horseback, with gifts of furnishings, food and clothing, previously purchased within the monastery itself. But that’s not enough. The superior performs a new blessing on some jewellery. Effigies depicting the founder and rags with ritual designs, which he distributes against payment of a fee. This is the last act of the quest, a voluntary offering that the younger monks themselves and some of those living inside the monastery pay.

It is well understood that maintaining a large structure that includes stables for breeding horses, and several buildings housing the monks, roosters and other animals, is not cheap. It is more difficult to understand why all that outlay of money. If the monks already live on quests, they have sufficient resources to maintain the horses by having fields at their disposal and cutting wood, which they then sell. The same procedure is repeated from week to week alongside similar moments in the other villages. The questions arise on their own and the doubt of an exaggerated religiosity, sweetened by the underlying spirituality, remains.

That the opium of the people has no cultural as well as geographical or philosophical boundaries?