“Now you must explain to me why you want to enter the Villa?” – his voice left little room for indecision. Still, perhaps because it was accompanied by a figure who was anything but discreet, I could not hold back a natural instant of hesitation.

“Because beauty starts from the bottom,” I reply, looking him straight in the eye.

We are the same height, but he is undoubtedly larger. And even older. Dark eyes of those who have seen things experienced them, and understood many of them. Or at least accepted as a natural part of life. For a moment, we look into each other’s eyes, staring. I do not understand whether his thoughts are of acceptance or pity towards me.

“That’s a ridiculous answer”,– he says almost politely, but I realise that the look from before was probably not one of approval. “Be at Tapia’s, the Comedor, at noon, on Sunday, then we’ll see.”

These were my first words with Ricardo Capelli, a trusted friend of one of the most charismatic and significant figures of the wretched in Buenos Aires: the late Father Carlos Mujica, an Argentine priest and professor who was among the forerunners of pastoral work in the slums of the metropolis and who, after dedicating his entire life and apostolic mission to the poor of Villa 31, was killed in an ambush on the evening of May 11, 1974, as he was leaving Mass in front of the porteña church of San Francisco Solano in Villa Luro. Fourteen gunshots. Many of these straight in the face as if it were an execution. In the same ambush, Ricardo, the only witness alongside Father Mujica, was shot four times but miraculously managed to save himself after a lengthy hospitalisation and eight operations.

At that time, Argentina, fresh from several military dictatorships and many crises of the welfare state, found in the Peronist policy a utopian glimmer of hope, albeit praiseworthy, to fight against poverty and to give dignity to labour. Two months after the assassination of Padre Mujica, a Buenos Aires still reeling from what happened wakes up to the death of one of the most beloved – even if controversial – presidents of the 20th century: Juan Domingo Perón, husband of that Eva Duarte – known to all as Evita – who managed to stir up the entire Argentine people and its working class from the balcony of Casa Rosada in Plaza de Mayo.

It is the dawn of one of the saddest and bloodiest pages of Argentine history. Isabel Martínez de Perón, already vice president, takes the country’s reins and becomes the first woman in the world to head a republican state. His government, however, ended very quickly on 24 March 1976, with a coup led by General Jorge Rafael Videla, following increased violence, social unrest and economic problems.

From that moment on, Ricardo Capelli, already a supporter of Padre Mujica’s work, became an inconvenient witness to his death and political executors. For this reason, he was persecuted, threatened several times and imprisoned as a desaparecido prisoner in 1978. After some time, he plucked up the courage. Finally, he denounced the material author of the murder, commissioner Eduardo Almirón of the paramilitary group Tripla A (Argentinean Anticommunist Alliance), linked to the Ministry of Social Welfare at the time, led by the writer and policeman José López Rega, formerly an influential confidant of the Perón couple.

Clusters of hope

They are called Villa Miseria, or simply Villa, and they owe the origin of the name to two schools of thought: one romantic and typically Italian, the other more accredited.

According to the romantic one, the name (Villa) derives from the innate irony of the Neapolitan immigrants who, in the early twentieth century, found themselves working on ships docking in nearby Puerto Madero-now one of the most elegant and modern neighbourhoods of Buenos Aires. Having no possibility of housing, forced to dwell in shacks along the tracks of the nearby Retiro San Martin station, the tani began to call their homes “villas” to poke fun at themselves, given the condition in which they lived.

But it seems instead that the name was taken from Bernardo Verbitsky’s 1957 novel “Villa Miseriatambién es América” (Villa Miseria is also America, ed.) where he describes the terrible living conditions of internal migrants during the so-called“Década Infame” (1930-1943).

Villa Miserias are spaces of urban segregation. Barrios enclosed within the metropolis, created after the first migrations from inland and, above all, from Europe, at the beginning of the 20th century. Villa 31 was built in 1930 and is the oldest of these villas miserias in Buenos Aires. Although going through different processes, including some sporadic attempts of urbanisation or uprooting, the villas are still self-built neighbourhoods, mainly lacking in basic infrastructure and services (roads, electricity, water, a sewage system, …), increasingly populated spaces where crime, local mafias and drugs find fertile ground for expansion.

With the fall of the military junta and the many political and economic crises, the government that seemed to have a real vision for a solution to the villas problem was the Peronist government of Néstor Carlos Kirchner at the beginning of the new millennium. Again, history seems to be repeating itself. At the premature death of the president, his dynamic and energetic wife, Cristina Fernández Kirchner, takes over the reins of the country For eight years, she ‘sold’ her social development policy to modernise the villas to transform them into a barrio so that they became real neighbourhoods with services included in the urban development plan.

Even if it is often more politics of façade than substance, the president gains support and enthusiasm from the working class, as already happened with Evita. The idea of Peronism, however, is now old and the only reference anachronistic. Thus an even more personal and extreme idea was born: Kirchnerism. Actually, not very effective against the Villas because Cristina Kirchner’s national directive clashes with the right-wing government of the Ciudad Autonoma de Buenos Aires, led by the conservative Mauricio Macri, her great opponent.

And it is precisely the conservative government that represses, often violently, any attempt by the poorer classes to occupy the land. And this condition of repression and growing unsatisfied housing needs has given the rise in recent years to a housing struggle movement involving villa dwellers and the youth of the Ciudad.

It was not until 2019 that the city government, following the directives of the national government, agreed on a huge redevelopment of the Villas, including a census of their population.

El Sol de Mañana

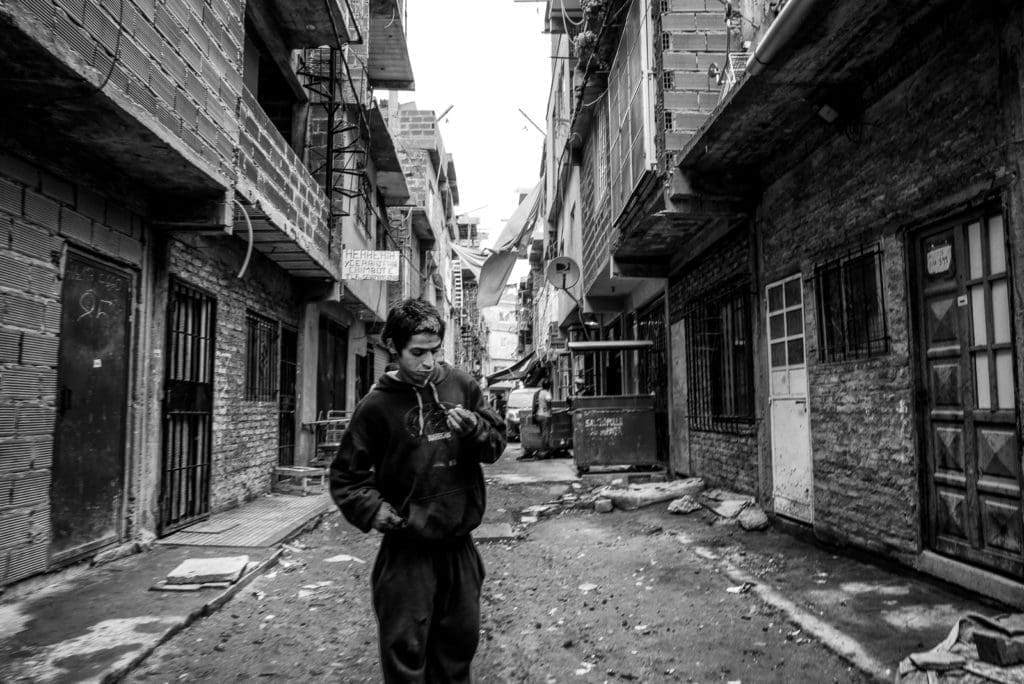

El Sol de Mañana is an encounter with the lives, the smells, the mud, the hopes and the passions of these people who live swallowed up by a metropolis that seems to deny any space to them.

It is the sun of tomorrow, rooted in the hearts of Argentines, for whom the Patria is their home, their barrio, and the community they belong to. And with melancholic hope, they entrust to tomorrow what they have not yet had today.

The project was realised within Villa 11-14, San Lorenzo and Villa 31, an urban agglomeration bordering the historic and elegant Retiro barrio to the north and the modern and luxurious Puerto Madero to the south. Today Villa 31 has a very heterogeneous population of about 60,000 people, made up not only of illegal immigrants but also of young porteñe couples who cannot afford any other housing solution within the metropolis.

There is a phrase by Ricardo Capelli that I still carry with me: ‘Who is hungry, eats slowly’ and inside the Villa no one is in a hurry. Although everyone seems to be going somewhere, most of the time they just go around, putting off until tomorrow the idea that something might still change.