There is a moment, crossing the infinite expanse of the Mongolian taiga, when time seems to stand still. The sun filters through the branches of the larches, the wind carries the pungent smell of resin, and an almost primordial silence envelops everything. Then, suddenly, the sound of hooves on the ground announces the presence of the reindeer. A whole herd moves compactly between the white tents of the Tsaatan camp. There is no hurry in their steps, no hesitation. They know that this is their home. The Tsaatan are a people with no fixed roots. Their camp changes location every two or three months in search of new pastures for the reindeer. They dismantle their tents as carefully as they put them up, load everything onto their animals and set off again. Their being nomads is not a choice but a necessity. A necessity dictated more by the reindeer than by their needs.

Their dwellings, similar to the Teepees of the Native Americans, are built with wooden poles and white cloths, leaving an opening at the top to let out the smoke from the stove. Inside, space is reduced to the essentials: a low wooden table to prepare meals, a small food pantry, and beds made of planks covered with heavy woollen blankets. When the temperature drops below zero, warmth in the tent becomes essential, even in summer. The thin metal box stove burns wood quickly and heats the tent within minutes. But as soon as the fire goes out, the frost takes over every corner. So one huddles under the blankets, waiting for the new day.

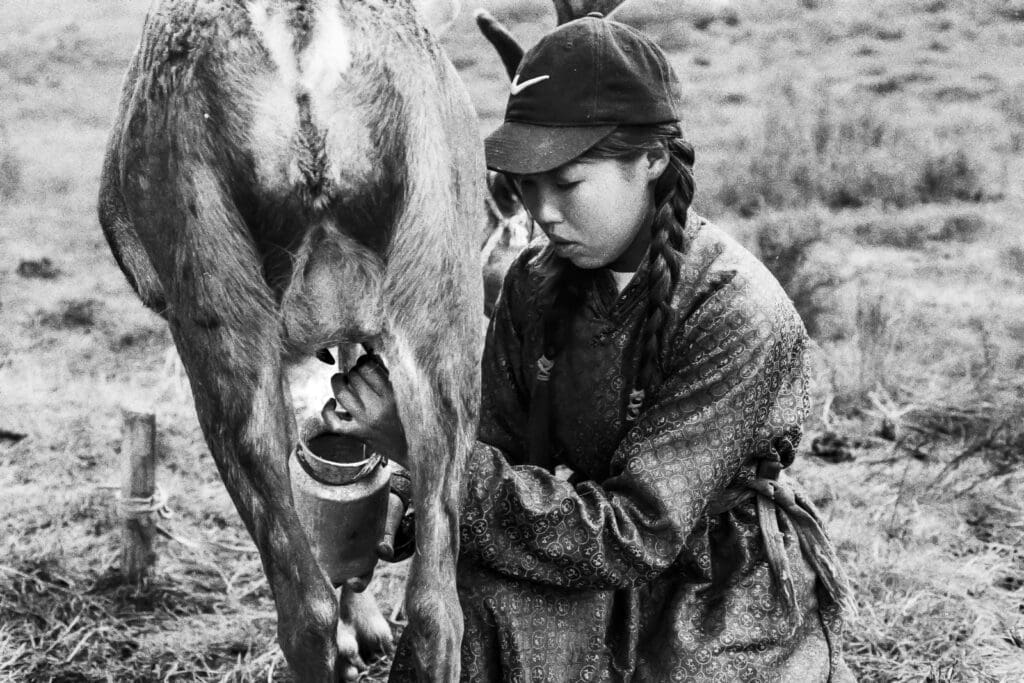

The Tsaatan’s close relationship with the reindeer

Each day in the Tsaatan camp begins with milking. The reindeer are rounded up at dawn, their front legs bound to prevent sudden movements, while expert hands collect the milk in an aluminium bucket. Reindeer milk is at the heart of the Tsaatan diet: used for milk tea (hot tea made from reindeer milk), processed to make cream and butter, or stored in plastic bottles. Here, nothing is wasted; everything can and should be reused. Reindeer meat is also valuable. No young animals are slaughtered, only those too weak to move or victims of wolf attacks. The meat is cut and hung on long ropes in the trees, left to dry in the taiga wind.

The day is also conditioned by cutting wood, which is essential for heating. It starts with large logs and ends with small, thin pieces used to light the stoves.

In the heart of the tent, a woman slices meat and onions on a wooden log used as a cutting board. There are no tables, no chairs. People cook squatting on the ground, stabilising the table with their knees. Over the fire, a cast-iron pot simmers with reindeer meat, potatoes and a few carrots. The few vegetables arrive from the nearest town, Tsagaannuur, a four-hour journey by horse or reindeer. And it is precisely the reindeer, compared to horses, that are the preferred means of transport for tackling the snow. Their broad hooves prevent them from sinking, ensuring faster and safer travel.

The risks of living in the taiga

Eating is a time of sharing. We sit on beds, legs crossed, passing steaming bowls and thermos flasks full of milk tea. The meal is simple and essential but always abundant. Alongside these everyday actions, other small gestures of daily life are revealed in their purest essence. An old man shaves his beard in the middle of the taiga, next to his cattle. With a razor blade and a cup of water, he looks at himself in a small mirror and slides the blade across his cheeks with slow, precise gestures.

Life in the taiga also has its risks. One night, a howl rips through the silence. Wolves are lurking, watching the camp from afar, waiting for the right moment to attack the reindeer cubs. The Tsaatan dogs know this; they have been fitting them for days and are more alert than usual. They bark, run around the tents, and try to ward off the threat. Sometimes they succeed, sometimes not. A reindeer cub is wounded, but its condition is too severe, so the next day, its meat is slaughtered and used for a meal.

A thin thread

The Tsaatans are not cut off from the world despite their archaic life. The village connects to the rest of the planet for one hour a day. The Mongolian government has provided them with the Starlink system. This dish picks up the satellite signal and allows them to send messages and download information and film for the children. We see a man sitting on the grass, an old mobile phone in his hands, watching it, switching it on and waiting. A subtle file links them to the outside world, applicable in an emergency.

The energy to power phones, radios and light bulbs comes from a car battery recharged by a small solar panel. It is little and is used sparingly. It is used to check the weather forecast, to receive news from the fields studying in the city and to light their tents.

We do not know how much longer this way of life will endure. But as long as there are reindeer to drive through the taiga, milk to be milked at dawn, and meat to be dried in the wind, as long as the stove fires burn in their tents, the Tsaatans will continue their journey.