We had stopped in Comodoro Rivadavia for the night, then spent al fresco among the aisles and altar of the church of San Cayetano, guests of the local community. Abel, a man of indefinite age, was there when we arrived by now with shadows stretching across the road, which that day seemed to go on forever. He and his band of dogs came to greet us. They had seen us coming from the newspaper shack in a flowerbed between two streets, right in front of the church, where they were all sitting together.

Abel and his dogs were there the following day as if the night had never come. He spoke semi-unintelligible Spanish but with grand, eloquent gestures. He proudly told us about his dogs. “Whoever is the enemy of one of them is also my enemy,” he told us seriously. His eyes, however, moistened shortly after that when he mentioned one of them who had passed away some time ago. Abel sells newspapers and sings. She has a powerful voice; you can hear her in the air from one end of the barrio to the other. He dedicated a song to us when it came time to leave again. His voice was firm, but his eyes were moist again. Shortly before, he had given some of us one of those small calendars that neighbourhood stores make as advertisements. The year wasn’t necessary; it doesn’t even say. It was the picture on the other side that was the valuable thing. Before giving it to us, he looked at our faces individually as if to peer inside us and carefully chose which image to give to whom.

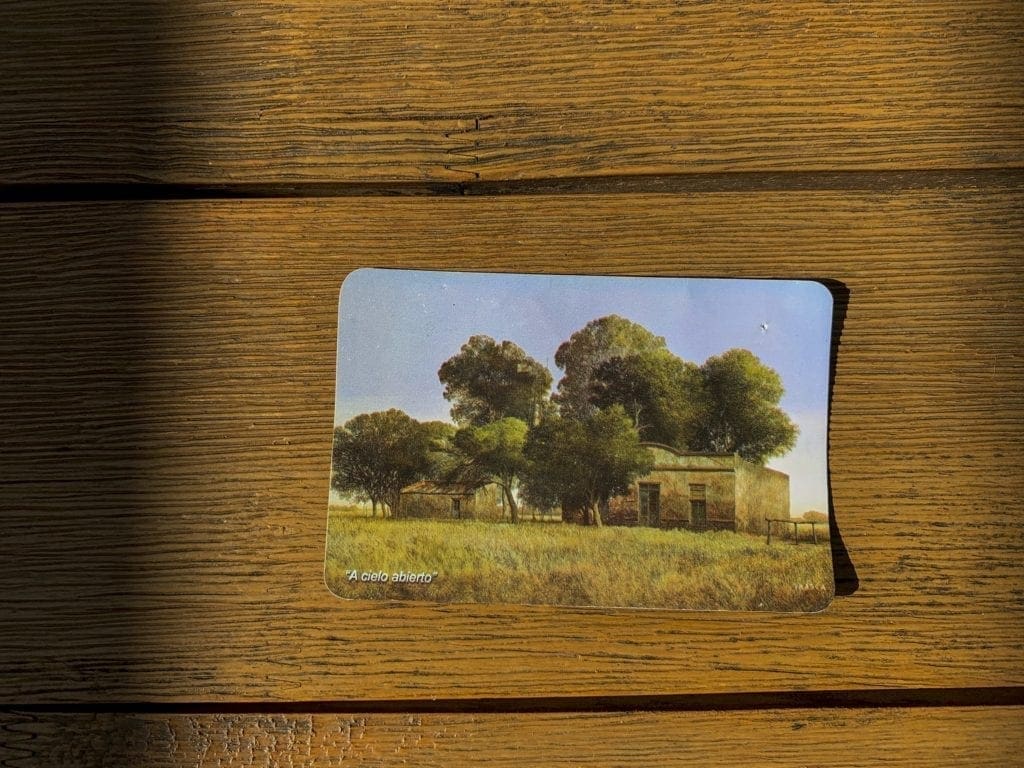

In my hands, he placed a scene depicting a landscape, trees and a farmstead, with the words “A cielo abierto” [sotto il cielo aperto]. And he could not have guessed better that, among the images he had, was the only one I could wear quickly. Shortly afterwards, again with moist, glistening eyes, he greeted us amid the barks of his street family. Even now, if I close my eyes, I can hear the sound of the engine and see Abel’s hand waving in the heat of the early afternoon, in a gesture that was meant to be more of a goodbye than a farewell.

The stories I want to tell

I returned a few months ago from a memorable trip to the Global South, and I did it in a country in lockdown. That may be why a book I had read several years ago came back into my hands: Latest News from the South, by Luis Sepúlveda, with photographs by Daniel Mordzinski. I started rereading it in no particular order, simply flipping through those pages full of stories and letting them tell themselves in no specific order: The Miracle Lady, the Tano, the Leprechaun, the last trip of the Patagonia Express…

“All the stories that follow are undoubtedly surrounded by the aura of the inexorably lost, because of that ‘inventory of losses’ that Osvaldo Soriano spoke of, the cruel price of our age. As we travelled aimlessly, without set times, without compass or other traps, the formidable mechanics of life that always brings together those who resemble each other led us to encounter many of the ‘barbarians’ alluded to in Kostantinos Kavafis’ poem. Their dreams were fearsome, so they were annihilated or pushed back into specially chosen extreme territories, but they continued to sow insomnia among the lords of power, who were increasingly obsessed with the danger of their return ordered banks to discredit them, and complete lunatics to write books about the ‘idiocy of the barbarians.’ And the ‘barbarians’ responded by planting forests, imagining an alternative to the dehumanization of the prevailing system, by organizing life so that living was a little more than a verb.”

– Latest news from the South, Luis Sepúlveda, p. 14

At the same time, another book jumped into my hands: Rebels! written by Pino Cacucci, who in real life is a friend, hermano, of Luis Sepúlveda – and I deliberately use the present tense even though the ‘wandering Chilean‘ sadly left us a few weeks ago, because some ties transcend life, or death.

«The rebels I have always loved are incurable utopians, animated by a lower-case utopia: not the utopia of grand ideals with which to change the world and establish the perfect society – thus risking contributing to the worst of nightmares, namely an Orwellian totalitarian system – but the utopia of the instinctive, irrepressible need to rebel. And even when defeat now seems inescapable, when reality would like to force them to accept a compromise to ‘save what can be saved,’ they continue to fight for what Victor Serge called ‘the impossible escape.’ Knowing that there is no escape in this world was not enough to convince them to give up.» – Ribelli!, Pino Cacucci, p. 9

These are the stories I want to tell in DooG Reporter: stories of ‘barbarians’ and rebels, dispatches from a world that will no longer exist in an indefinite time but that deserves to be known.