We arrive in Ardesio that has just gotten dark.

At this hour the town is but a clump of dark houses speckled with yellow lights: the silhouettes of a few bell towers peek out from the roofs like sharp pencils, all around the dense mass of mountains looms over the valley, black black as only conifer slopes know how to be at night during winter. From the car, it feels like being swallowed up. As you drive up from Bergamo along the Seriana Valley, the road slides past warehouses and cement flows that, from time to time, take the form of squat houses or ugly industrial constructions close to the river. But then suddenly, you go uphill; in front of your windscreen, you begin to glimpse the sharp, snowy silhouettes of the Orobian Pre-Alps, the valley of industry reluctantly gives way to the mountain valley, and the road becomes thin and sinuous, ever darker. It is not difficult to imagine the beauty of these views on a sunny day: but it is late January, the sun has long since set, the darkness is dense and icy, and the deserted road leading to the Orobic village does not give an idea of the chaos we will soon encounter in its twisting streets.

A propitiation ceremony

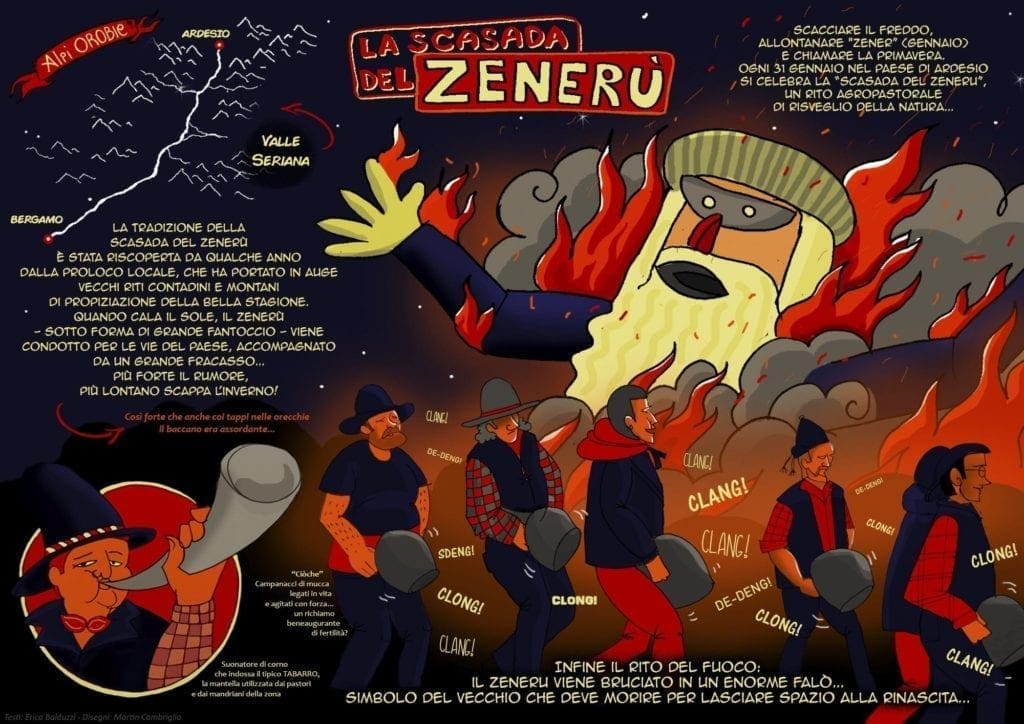

On 31 January, in Ardesio, the ‘Scasada del Zenerù‘ is celebrated: literally, the ‘eviction of big Jannuary’ (zenèr, in Bergamo dialect, means January, and zenerù is its augmentative or pejorative, depending on the interpretation).

Part agro-pastoral rite exhumed from the past and part tourist event, part tradition and part folklore, the Scasada is first and foremost a great moment of aggregation for the whole village, an occasion to remember the peasant and pastoral roots that here, in defiance of all the talk about how modernity hurts historical memory, the people are happy to claim proudly.

And you can already tell by looking at the people who gather at a brisk pace: many of them are young, young men and women with smartphones in one hand, a cigarette in the other and a large cowbell tied around their waists, and in the clangour of the metal they gather, laughing and making noise around the giant puppet representing the Zenerù before the parade starts and the actual event begins.

The Scasada del Zenerù is linked to popular mountain rites that, in peasant societies and valleys throughout the Alps, celebrated the end of the cold and the arrival of spring; Propitiatory ceremonies to reawaken nature, chase away the cold and invoke the excellent season which, between the days of the blackbird and those of carnival, staged a collective ritual with masks, noise and fire to exorcise the fears of winter and evoke the cyclical need to ‘kill’ as a community what is old to make room for the new. Elements that also come back in the Scasada of Ardesio, in the form of the puppet of the Zenerù – which every year in different guises is led through the streets of the village before being burnt at stake – and the clanging of the ciòche, the cowbells that herders used to put around the necks of cows during the transhumance and which today are tied around their waists to shake them more easily, in an apparent reference to the theme of fertility, both human and of the earth.

Send away January

When we reach the clearing from which the parade will start, people still arrive in groups: they huddle together, approach the float with the puppet (which this year depicts the Atalanta goalkeeper), study it, laugh, and have their photo taken. You can hear the clong-clong of a few unconvinced cowbells; it sounds more like a rehearsal or a quality test, and the real commotion will come later.

It is cold, many huddles in coats, many others in long, dark woollen tabards fastened at the neck with a silver buckle: these are the cloaks worn by shepherds and herders in the highlands, made of thick, warm wool, and in these parts, they are experiencing an inevitable stylistic revival. We envy them a little: our light windbreakers are not suited to the sharp air coming down from the high valley. But, on the other hand, the youngest are also the warmest: they wear the latest jeans and plaid flannel shirts, take selfies and then shake the cowbell they have tied around their waists with a lived-in air, the louder they make noise, the more fun they have. The air smells of anticipation, it is filled with laughter and the cadenced vocalizing of these parts; those who arrive are greeted in narrow dialect, big pats on the back and loud calls pass by, which are intertwined with polite but detached glances toward those who, like us, are blatantly furestèr, that is, outsiders, not from the country. The edge is thin but sharp: we participate, and you watch, says that edge. And to watch a lot of people came, from the neighbouring villages and the city of Bergamo, almost 50 kilometres further down the valley: the pro loco works well, the Zenerù has been publicised since December and attracts more and more tourists and onlookers year after year. Perhaps that is why some locals turn up their noses, saying that today’s Zenerù has little to do with that of the past. Too many people, they say, too many invitations to popular groups that have nothing to do with the territory. Too much folklore that makes colour but does not make culture or memory.

Whether this is true or not, the people crowding the square care little. The sound of cowbells has now been joined by the sound of horns made from the horns of beaks (instruments used in ancient times by shepherds and peasants to call out to each other at a great distance). Still, the din of those lacking traditional tools have brought pan lids or empty cans tied together with string: anything goes, as long as it makes noise. One turns around the puppet as if paying homage to a pagan idol. «The noise is to drive away the winter! – explains an enthusiastic and sinewy shepherd, who wears a cowbell as big as my chest tied to his waist and swings it as if it were a small bell – the louder you make it, the sooner spring will come!» And as if to convince me of this, he shakes the cowbell with conviction, immediately followed by the few who had not yet started making a racket and the children who want to participate in the general atmosphere of excitement.

The fire ritual

By the time the Zenerù parade gets underway, there are several hundred people in the square, the noise is loud, and the crowd is too. This year’s invited folk group leads the procession, the Boes e Merdules from Nuoro. The clangour of their traditional costumes adds to that of the locals; in a roar, alley after alley invades the village and the courtyards, filling the ears and excludes everything else.

People follow the procession, take the mulled wine offered in the clearing, and look out from balconies and terraces; those who can participate briefly with their hands cupped over their ears. But it is the bonfire that is the real highlight of the event: it is there that tempers flare, and it is there that the young cowbell players rediscover a wild spirit for a few moments. While the flames envelop the Zenerù and stretch hot tongues towards a mountain sky full of stars, all around is a frenzied dance, a tribal ritual, a return – at least for a little while – to what these valleys must have been like many centuries ago when nature and not man was in command. It is only a moment, lasting a few minutes.

Then the wind turns the flames, scatters scorching lapilli on the crowd attending the bonfire, disperses it within minutes. The party’s over, it’s time to go home, to hole up in the warmth after braving the great cold of late January.

Ardesio empties out, and for us too, ears aching and head full of roar, it’s time to head back down into the valley.