While living in Johannesburg I met many workers, each of them with a unique story, but similar at the same time. They all had one common denominator, work, and they all ended our chat in the same way. Many of them are immigrants and these few pages are only a small part of a much larger story, a whole world of sacrifices, cultural aspects and dreams. These workers moved from their countries of origin to South Africa in search of a better future for themselves and their families. Often they had to leave their families behind to take the risk alone. Other times, relying on God, they moved with the whole family. Some have official documents and can aspire to regular employment. Some use a relative’s document in the hope of not being discovered. Others have entered illegally, often crossing the border at night through national parks, braving the danger of wild animals.

For these people without proper papers, life is much harder and someone specifically asked me not to photograph him near his home. Among these migrants are skilled workers, highly educated people, but also people in need. To find work, many of them spend their days at traffic lights or in front of work material dealers, displaying handmade signs in which they write their skills, sometimes true, sometimes less so. For these workers there is no Saturday or Sunday; we will always find them in the same place every day, waiting for someone to hire them for a day’s work or perhaps for a longer period. At sunset, they return to their homes, very often to the nearest shantytown, in which they just as often share a small dwelling built with salvaged material, without running water or electricity. These people, these thousands of little ants ready to do anything to give their families a future, are the real driving force of the city of Johannesburg. Years of sacrifices were made to improve their conditions and with a dream common to all: to return to their home country to spend the rest of their lives there in serenity.

Mediator Moyo | A gardener in Johannesburg

This is Mediator, he is 37 years old and from Zimbabwe.

He works as a gardener in northern Johannesburg, in the homes of wealthy families living within the compounds. Cutting grass, taking care of plants and pruning trees is his main occupation, but he is also often asked to take care of small maintenance jobs and clean the swimming pool. He lives in Diepsloot, a huge township situated in the north of Johannesburg. Mediator does not have a proper house but lives in an Umkhukhu, the name in the Zulu language given to shacks built with makeshift materials. Barracks are sometimes simple shelters barely big enough to hold a bed and a few buckets of water and a few things hanging on the walls in plastic bags. Electricity, as well as running water, are only a mirage for many of the slum dwellers.

Small solar panels are the only source of energy they can aspire to and Mediator, with his, powers a small radio that keeps him company. Much of the money he earns is sent home to Zimbabwe where he left his family, a wife and three children whom he will not raise and whom, because of the high cost of travel, he only sees once a year. The money he saves is used every year to expand his current flock and to achieve his dream of finally returning home and starting his own breeding business. Throughout his years in a foreign land, he has alleviated loneliness and lack of loved ones by finding companionship in the neighborhood, where other people’s families have also become his family.

Mediator is one of many workers in the city of Johannesburg.

Shupi Kay Chuma | A maid in Johannesburg

She is Shupi Kay, a 34-year-old maid from Zimbabwe. She lives with her family in Krugersdorp, a township about 60km from Johannesburg. They live in a nice three-room flat in a building in the city centre; it is small but cosy and, most importantly, they can pay for it. Shupi Kay and her husband have known each other since kindergarten. They got married in Zimbabwe and had their first daughter in 2004. A few years later they decided to move to South Africa. Leaving Zimbabwe was a very tough decision for them, but the lack of work and the precarious state of the economy led them to decide to leave and seek their fortune elsewhere. In April 2017 in Johannesburg, they became parents for the second time. Every morning Shupi Kay takes a local minibus and takes about an hour to reach the homes of the clients for whom she works as a maid. Like many African women, for the first few months she worked with her daughter lying on her back, but week after week the child grew, the weight increased and the work became more and more tiring.

Although she did not agree, she had to resign herself to the idea of leaving the child at home and looking for a kindergarten for her. An expensive situation but one that allowed her to continue working. In addition to her two daughters, Shupi Kay also often has to take care of her sister’s son (4 years old). Unfortunately, the mother often works at night and it is difficult to match work schedules with the baby’s needs and sleep. But Shupi Kay has a plan for the future: she dreams with all her might of stopping working for others and opening her shop. Most probably she will sell second-hand clothing because she has a great passion for fashion and clothes. The greatest wish for Shupi Kay and her husband, however, is to see Zimbabwe great again and to be able to return home with a real chance of creating a job there that can support their family. They both hope it will happen within a couple of years, but for now, Shupi Kay is one of many workers in Johannesburg.

Rodney Nkwana | A street hawker in Johannesburg

He is Rodney, a friendly street trader from Pretoria.

He is 27 years old and lives with his mother, sisters and a long list of relatives in Klipgat, in the northwest of the city. Every morning, with commendable constancy, he takes a local minibus and reaches his ‘office’, sometimes after two and a half hours. This is the name he gives to the intersection where he works in Johannesburg and where you can usually find him if you need him. Near that crossroads, from the morning at 10 am to the evening at 5 pm, he sells hats, which he in turn usually buys in a warehouse, at a good price. It is not easy to do business with a single article, but despite this, Rodney does it well. With her job, she not only supports herself but also manages to help her family because, after her father died of HIV, it was necessary to help her mother with household expenses.

But what is the secret of its success? Rodney has a good memory and remembers everyone. And for each one, he has a few dedicated words and a big smile.

He is bright and on a normal working day, you will most likely see him running towards you and saying ‘I’m running like a horse, Bozza‘ (South African slang for Boss). At other times, when the traffic lights are out, you’re sure to hear him say “I’m taking advantage of the situation!”. And suddenly, when you’re about to leave, he reminds you to come by his office again to look at the new collection for the next season. Rodney started working at the age of twelve as a peeler in a fast-food restaurant in the neighbourhood where he lived. After graduating, he opened a hawker shop at the crossroads of the city where he sold snacks and cigarettes for years, a shop he left to friends in 2011 when he decided to start his current business. Rodney has business in his blood and is a confirmation that intelligence, willpower and perseverance can create work where it does not exist. In a decade or so we might see him as the CEO of his own company, but for now, he is just one of many workers in Johannesburg.

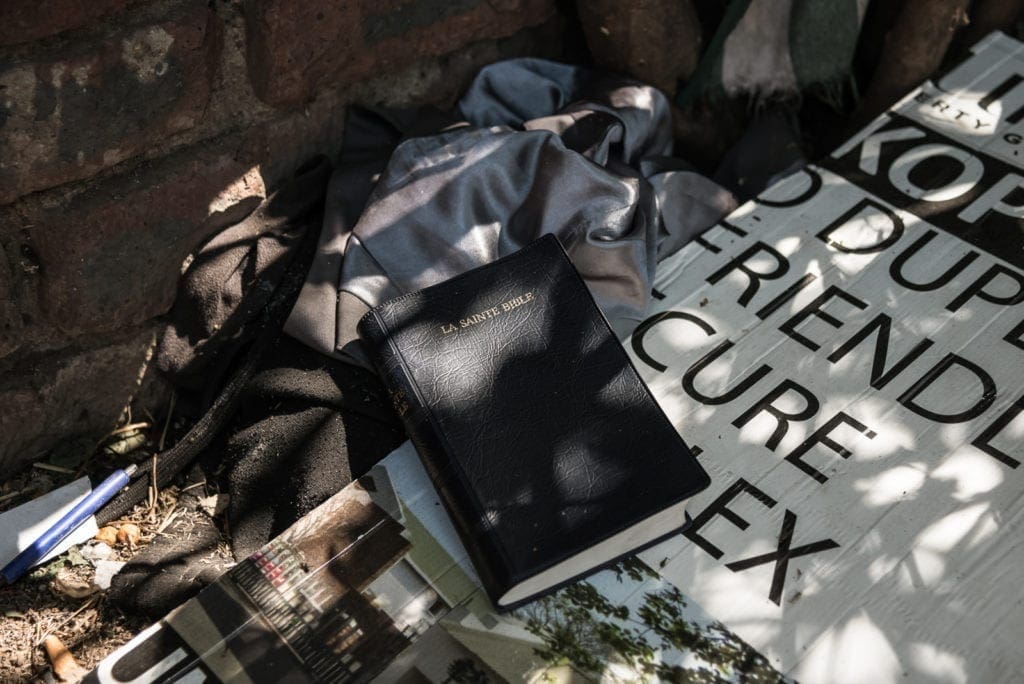

Brighton Moyo | A homeless man in Johannesburg

This is Brighton, he is 33 years old, from Zimbabwe and homeless. Before leaving Bulawayo, the city where he lived, he was a mechanic with more than ten years of experience. Due to the huge devaluation of the local currency and the resulting increase in inflation, he decided in 2015 to join his brother in South Africa and look for a new job. He arrived in Johannesburg in 2015 and immediately found work in a garage as a mechanic. Everything seemed to be going well: he had a job, his own space inside the garage in which to sleep and money in his pocket to live a good life. At the end of 2016, however, everything changed and his life began to fall apart. After his brother died of illness, Brighton had an accident at work: during a trivial manoeuvre, he lost part of a finger and had to stay in hospital for a few days. Annoying and painful, but nothing so serious, it was not life-threatening.

When he was dismissed he returned to the workshop but found it empty and all his belongings gone. In all likelihood, the owner, frightened by the legal and financial consequences of the work accident, decided to move everything and disappear. The end of the story is simple: Brighton lost his job, his housing and all his belongings, including the tools he worked with, and became homeless. He now lives near a crossroads, the only place he knows; he has often had to change where he camps because no one wants a homeless person near their home, and he survives on donations from people he meets. He hopes to soon find a place to live and a suitable job, perhaps as a mechanic, but for now, Brighton is one of many workers in Johannesburg.

Samantha Kumeni | A chef in Johannesburg

She is Samantha, a 31-year-old young woman from Zimbabwe. After many years in a petrol station, he decided to open his own business. The idea was to take care of something that people couldn’t help but buy, and since 2010 he has been cooking and selling food in his roadside caravan. Every day he cooks two different kinds of meat, seasonal vegetables and the ever-present PAP, the main food of the southern African people. It is simply maize flour cooked in hot water, often with little flavour because salt is expensive; it is considered the common substitute for bread, fills the belly for a long time and is very cheap. Samantha moved with her family from Bulawayo to Johannesburg in 2004. Once she arrived, she met her current husband who gave her two children. Unlike many Africans, they have a house in a compound close to where they decided to park their caravan. This makes it easier to transport food from home to work and also reduces the time spent on the road.

At home, he prepares the food and in the small kitchen in the caravan, he finishes cooking it. She often receives bookings over the phone; this is a service she has decided to give so that customers choose her from the many street vendors in the city. Samantha is happy with her job and is thinking of expanding her business: buying another caravan to park in front of a newly opened construction site. And then, once the second caravan is found, hire someone to sell the food she prepared to the workers on the site. Samantha thinks that being your boss allows you to do what you want with your money. And, in this case, decide how to invest your earnings and efforts to grow in what you believe in. She really likes her job and is also sure that people will always need to eat, so this job will never be lacking. Samantha is one of the many workers in the city of Johannesburg.

Patrick Moeketsy | A craftsman in Johannesburg

He is Patrick, a 30-year-old leather craftsman from Lesotho. In 2006, he left his village in the Moorosi Mountains because he found his business too slow. Someone advised him to go to South Africa because only there would he be able to fulfil his aspirations. And so he did. He contacted his relatives, arrived in Johannesburg, and started doing what he was capable of doing. The work did not start as fast as he expected, but he had the strength and perseverance to achieve his goal. One by one the relatives around him all died and Patrick had to live through a very difficult time. In 2010 he decided to return to his mountains in Lesotho to try to heal his soul and decide what to do with his life. After some time he returned to Johannesburg with the specific intention of working hard and making his business work, and within a short time, he became one of the most renowned shoemakers in northern Johannesburg. He lives in the Diepsloot slum where he has his shop on the street but sells his creations throughout the city.

Everyone knows him as a true artist because Patrick can make a pair of shoes of any size, starting with the raw material and sewing everything by hand. Moreover, he is one of the few craftsmen in the area to guarantee his shoes for ten years and gives his customers the option of paying in instalments in two months. This is necessary because many of the people living in the slum are not so well off and its products are slightly above their means. Over the years he has designed and developed his lines of shoes for men and women, sandals, boots and even sneakers. His idea is to expand the business and hire at least one person to help him with the daily repairs, plus another who can help him with the mass production of the shoes. Patrick has a real aptitude for work and is a hard worker; these two characteristics will probably make him the future owner of his shoe factory. He is currently one of many workers in the city of Johannesburg.

Action Mtisi | An artist in Johannesburg

This is Action, a 40-year-old artisan from Zimbabwe. Like many other boys from his country, he left the capital Harare because of poor economic conditions. He arrived in South Africa alone in 1999 and worked for a while in a handicraft shop owned by a compatriot. He lives in Soweto, a huge urban settlement southwest of the city of Johannesburg and it was here, 15 years ago, that he met Maide, his South African girlfriend. For many years Action sold handicrafts produced by others, but thanks to his foresight and creativity, he decided to set up his own business and give freedom to his creativity. The place he chose to sell his art is the Bryanston Craft Market, an interesting area located at the intersection of three streets north of the city. In this triangle of land, Action, like many other artists, sells different kinds of products. In his space he produces and sells carved wooden statues and stone statues, products of his home country; garden furniture made of woven banana leaves and animals made of iron.

The latter are the real pride of his shop: Action and his brother ‘from another mother’ who arrived from Zimbabwe, can build any type of animal of any size. The materials used for their sculptures come from metal barrels used for oil or fuel, bought cheaply at metal collection centres. The barrels are cut, moulded on a metal frame and finally welded. Rust is the finishing touch that makes them unique. The process to make a life-size rhinoceros takes about two weeks and the work will be produced at a location other than the Bryanston market because the area does not have electricity. Action is thrilled to be part of Bryanston’s craft market artists, but laments the large, often unfair competition: many shops have the same items and the shortage of customers often drives prices down. Every day he squeezes his brain to come up with new ideas. Something is never seen before, to produce and sell in his shop. Action is a creative, artist and one of the many workers in the city of Johannesburg.

Paul Ndaba | A waste picker in Johannesburg

This is Paul, a 34-year-old young man from Lesotho.

Every morning he wakes up at dawn and pushes his trolley from the place where he lives, to the affluent neighborhoods of the city. In the city, weekly bins are placed outside the gates of the compounds to be emptied by the waste disposal company. Before this happens, Paul collects plastic, aluminium and cardboard, materials which he then resells by weight at collection points. Wandering from street to street with an increasingly heavy cart is hard work. Johannesburg is located in the mountains, there are always road works, traffic is often congested and, above all, the weather conditions should not be underestimated. Those who do this waste-picking job to defend themselves from the heat with what they have, but often those who, like Paul, come from Lesotho, use woollen balaclavas. This classic garment of the highland shepherds is useful for the cold mornings, and hot midday temperatures and for protection from dust on the road. At the end of a working day, if it went well, he can earn between 120 and 150 rands from the entire load, which corresponds to 8-10 euros. Thanks to some friends who were already in town, when Paul arrived in Johannesburg he already had a ready-made shelter next to his friends, encamped in a place on the road to Lion Park. These friends also prepared everything he might need inside to live on: mattresses, blankets for the night, water containers and even everything he needed to work the next day. He considers himself very lucky to have such good friends. Before leaving his country, Paul was a teacher for adults in the Berea area, where he lived. Being an unlicensed teacher meant being paid very little and the salary he received was not enough to support his family. He got married only four years ago and is the father of two children who currently live with their mother. Getting married at 30 for an African man is very strange, but for Paul the reason was simple: if you are alone you only have to provide for yourself. He decided to move to Johannesburg to earn as much money as possible and send whatever he could back home for his family. Although he had only been here two weeks when we met, he was optimistic and confident that he would earn more money from this hard work in South Africa than from working as an unlicensed teacher in Lesotho. Paul is one of many workers in Johannesburg.