The propagation of pandemics and their media coverage is cause for great concern. We see this these days in the wake of the spread of the Wuhan Corona virus “SARS-Cov2.”

The perceived severity of these phenomena is greater when we can see the consequences up close. However, the diffusion of these epidemics almost always originates in developing areas, in regimes where democracy and freedom of information are compromised, and it is precisely the opacity of the information system that is often the reason for delayed reactions by government authorities.

While the reaction of health authorities in developed countries is effective to a certain extent, this is not the case in poorer areas that are less well served by adequate health facilities and means of transport.

The H1N1 virus or ‘swine fever’

With the following report, I wanted to tell the story of the flu epidemic from this perspective. In 2009, a subtype of swine flu type A H1N1 was transmitted from some pig farms to humans, causing deaths in Mexico and spreading the disease worldwide. This variant has been called ‘swine fever’ in the media. Between 8 March and 2 April 2010, the Brazilian Ministry of Health carried out the second and third phases of the vaccination programme against the H1N1 virus, those dedicated to health workers, indigenous people in villages, and pregnant mothers and their children.

This photojournalism is part of a larger project dedicated to Brazil and was carried out at that time, in the state of Maranhão, mainly in the village of Mandacaru, a poor fishing village at the mouth of the Rio Preguiça, in the far north of Brazil, on the edge of arid yet fascinating desert areas that caress the rainforest.

In that area, the river had allowed for the development of a subsistence economy based on fishing and transient tourism, due to the lack of accommodation facilities and difficult connections.

The nearest city with adequate health services to the village was São Luis, the capital of Maranhão, about five hours away by boat and then by car or bus.

The vaccination programme in Mandacaru

Arriving in São Luis, a five-hour flight from Rio de Janeiro, I had, like others, found a private car providing transport from the capital to Barreirinhas, a river village on the edge of the desert. I had shared the journey with a young mother and her little Felipe, portrayed in one of the following photos. Felipe was suffering from a form of dermatitis. They had travelled three hours by car from Barreirinhas to São Luis, for a dermatological examination, and with me, they made the journey home. I understood immediately what unimaginable difficulties they encountered daily.

Leaving the capital, along the way, the living conditions of the people easily hinted at their economic and health conditions.

Arriving Barreirinhas in the evening, I boarded a riverboat the next day and reached Mandacaru.

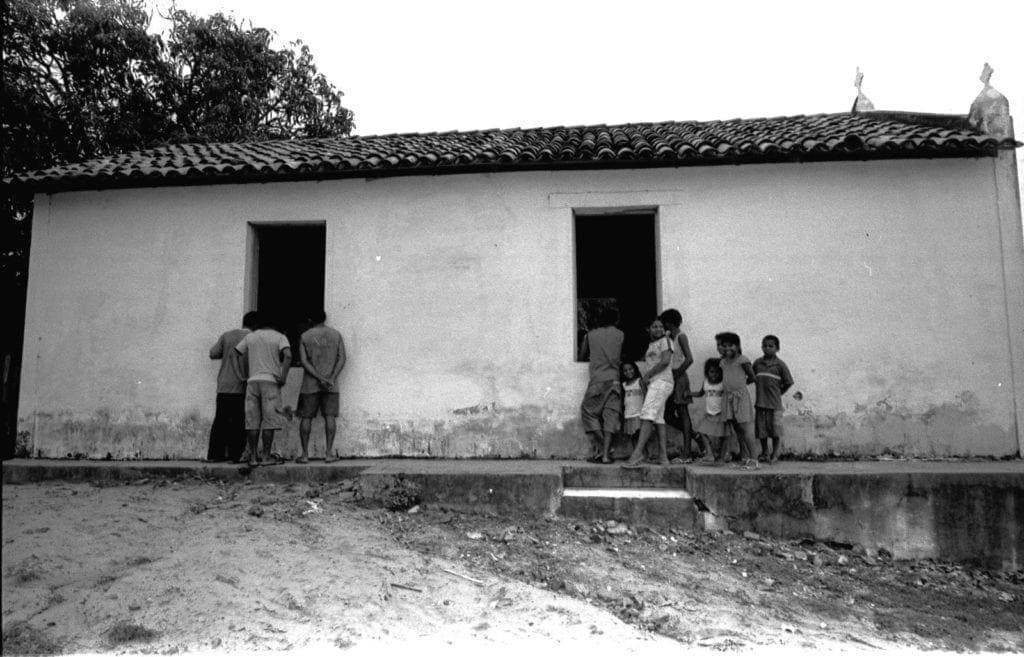

Among the brick houses and sandy streets, an outpatient clinic had been set up in the church of São Sebastião. The vaccination had rallied the entire community and initially concerned young mothers and children. The latter had, as always, found a way to turn the event into a moment of play. On the people’s faces, the signs of fatigue did not hide the serene and fatalistic spirit of these populations whose lives are strongly linked to the benevolence of nature.

This report is dedicated to the glances I have crossed along this journey.