Cambodia Journals | Phnom Penh, 06 September 2019

It was 1979 when Vietnamese photojournalist Ho Van Tay, led by the stench of rotting corpses, entered S21, or Tuol Sleng, which in the Khmer language means The Hill of the Wild Mango.

Once a second-grade school in Phnom Penh, in 1975 it was transformed into the main detention, interrogation and torture center of Pol Pot‘s bloody Khmer Rouge regime.

What Ho Van Tay-who was the first media representative to document what had happened at Security Office 21 (S21)-faced was nothing human. In the former school’s classrooms, in the first complex, metal beds turned into torture machines. Torn and mutilated bodies were still anchored with metal bars to the bed. The second complex turned into a detention centre with brick or wooden micro-cells. And entire rooms where prisoners were crammed to the floor in excruciating pain, left in the dirt of their own bodies.

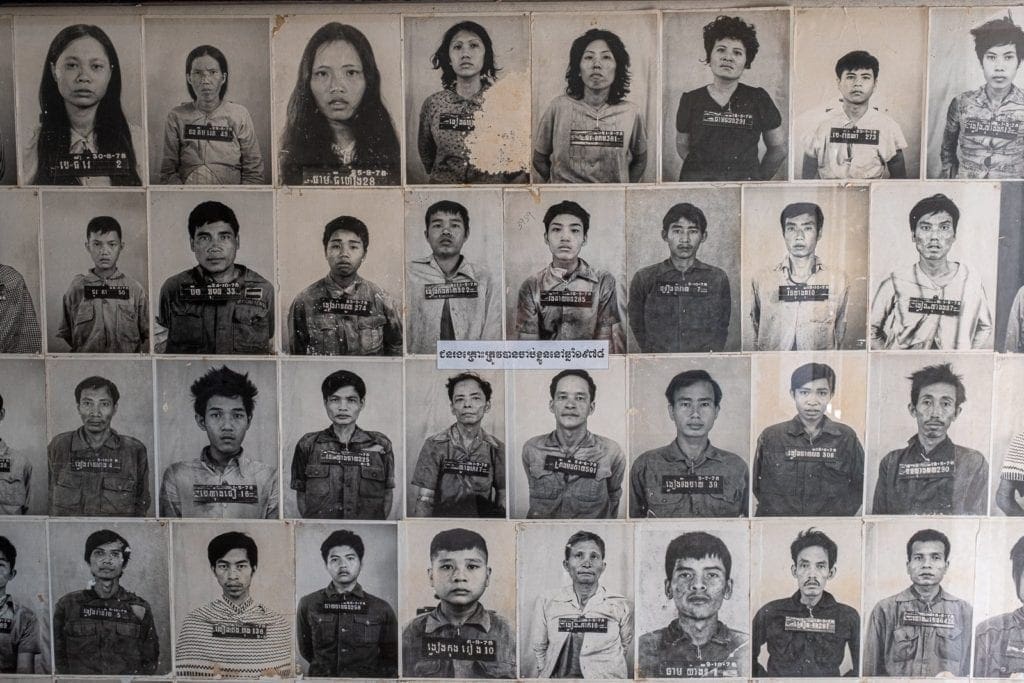

Another building contained the meticulously compiled records of all the prisoners who passed to S21, mug shots, interrogation records, notes of Mengele-style medical experiments.

Ho Van Tay was confronted with this, and from that moment on, the whole world could no longer continue to miss. He had to watch. It is estimated that around 20,000 people were taken to S21, and only seven survived because they were declared ‘useful to the party cause‘. The Khmer Rouge regime, between 1975-79, opened seven more detention centres equal to S21 throughout Cambodia.

During the International Tribunal for Crimes against Humanity trial, Comrade Duch, born Kaing Guek Eav, a prominent member of the Khmer Rouge party and head of the S21 detention centre, stated that those taken to Tuol Sleng had no chance of coming out alive. Whether he was guilty or innocent was just a useless formality. For every one of them to get out of S21 meant going to Choeung Ek, the Killing Field – Camp of Death 15km south of Phnom Penh and thrown into the mass grave with a stick shot in the neck or the back of the head “… because bullets cost too much for this kind of death”, as reported in Duch’s testimony during the trial on Feb. 17, 2009.

Note

During the trial, Kaing Guek Eav, although having in his first deposition admitted his responsibility, in November 2009 dismissed all charges against him by seeking acquittal, claiming that he had acted in compliance with “the execution of Pol Pot’s orders.”

On July 26, 2010, under the auspices of the United Nations, Kaing Guek Eav known as Comrade Duch, was sentenced to 35 years in prison.

Many countries directly (or indirectly) supported Pol Pot’s bloodthirsty regime that wanted a new Kampuchea, excellence in favour of the purest idea of worker-communist totalitarianism. And to create this new society, purified of Western and even Indo-Chinese idea and meddling, his plan called for the total erasure of the old society, budding generations included, in favor of the purest implementation of the Maoist idea.

A utopia that resulted in what history remembers as the Cambodian genocide.

Entering Tuol Sleng today

I entered the former Tuol Sleng High School early in the morning, when the heat and the last remnants of the monsoon season were not yet pressing on the body.

In 1980 it was turned into a museum, the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, and today it looks exactly as the Vietnamese army found it in 1979.

Cleared of the mangled and mutilated bodies in the school’s classrooms, no remediation or alterations were made to the structure. With an average of more than 500 visitors a day, and many of them Cambodians, the museum today is a reminder of human folly – whether it be of one person or of many who have found in this their reason for their animal outburst.

Walking through the empty classrooms, the microscopic cells, or touching the iron bars used to chain the prisoners is a sensation that slows your breathing. An unnatural silence, almost as if to capture the wailing, heartbreak, and stifled scream of those within those walls, which still screamed in the hope of getting out free but unaware that this would never happen.

You walk on those floors and wonder if the stains you see are just signs of the times or the blood that soaked the once colourful tiles. You step on those floors and watch where you put your feet in fear and respect of those who – having stepped on it before you – never came out again.

And in the end you ask yourself: why?