Sudden storm

Mary’s gaze [1] turns beyond Mtkvari, looking out from the balcony of her apartment, in Tbilisi.

“It was a brave choice, but also a dangerous one,” I confess to her. “Sometimes you just have to act, without thinking about the consequences,” she replies, aware even then that the gesture would cost her dearly. “We were trying to protect an ancient forest in my city, which was destined for felling in order to build a shopping center,” she recounts, as she sips her goblet of blood-red Karkadè, “Even before the event I knew that if they wanted to, they would find me.”

And they did.

As Vladimir Makarov’s daughter, a past minister in the Chelyabinsk region, her opposition to government policies was baffling, even to the arresting officers. “In the days following the protest, the authorities began to monitor my phone,” says Maria, pausing for a moment; her thoughtful look is marred by a scornful sneer: “A specific agency is charged with these probes, targeting individuals such as myself, labelled as adversaries and branded terrorists. They have the authority to inspect our residences and, upon finding any suspicious elements, to initiate arrests”.

Then came detention: eleven days without sunlight, then released. At that moment, she was unaware of the drastic changes her life was about to undergo in the ensuing months. “The announcement of the mobilization was the point of no return,” she continues. “The very moment I heard, I realized a difficult but necessary choice: leaving home, abandoning my affections, was the only way to continue to defend my ideas, you know?”

His voice is interrupted by a sigh: “Here at least I can still participate in a change that I believe will come soon.”

“What kind of change?” I ask.

“A change that no one expects, the kind that comes and sweeps everything away, like a sudden storm.”

A year and a half after his move, Tbilisi has presented itself as a space of freedom where he has been able to openly express his dissent and where, he says, people have shown welcome and compassion, although in recent months the situation has been changing.

The constant presence of Russian nationals is becoming a source of discomfort for a significant portion of the local population [2]. Additionally, Georgia no longer seems as safe a place as before. “Only a few days ago, a journalist was poisoned. [3] about ten minutes from where I live,” he confides. “I know that my freedom is just an illusion, and day after day, hour after hour, I feel that Tbilisi is no longer a safe place. I feel stuck as if I am still in prison.”

Across the border

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, more than one million Russian citizens have left the country [4]. Although many have returned throughout the conflict, a substantial number have stayed outside their national borders, and their presence remains evident in many of Russia’s neighbouring countries. In addition, the military mobilization initiated on Sept. 21, 2022, has intensified migration, abetted by fear for one’s safety and dissent, perceived by a part of the population.

Young generations, families, journalists, former politicians and activists have thus established a new home in countries such as Armenia, Kazakhstan and Turkey. Prominent among them is Georgia, to which more than a hundred thousand Russians have emigrated permanently [5] – complicit with the ease of entry into the country-bringing with them a baggage of mixed emotions from which new ideals are surfacing, bridges that are contributing to the development of civic initiatives in both Georgia and Russia, not without difficulty.

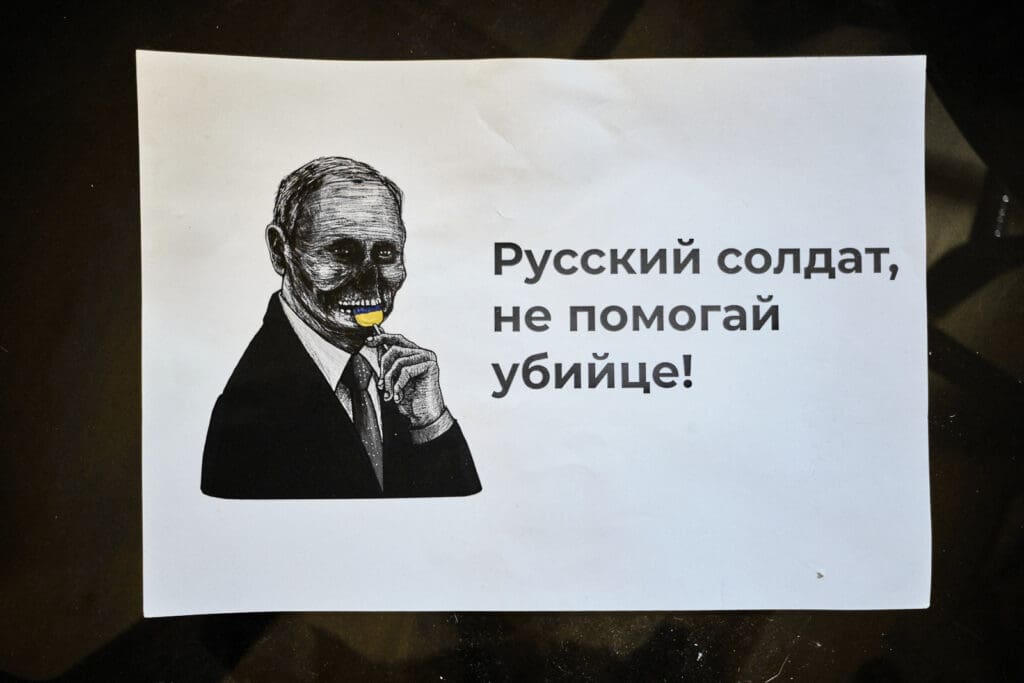

Marked by a history of wars and struggles for independence in the regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Georgia does not seem to offer the Russians a warm refuge. Walking through the streets of the Caucasian capital, every wall seems to remind him, painting a picture of distrust and anger, the result of a tangible reminder of the still open wounds between the two peoples. Flags of Ukraine and Europe are displayed from the balconies of homes, which are often flanked by white and blue flags, born out of a feeling of protest, silent symbols of representation of a large segment of Russian citizens who have made Tbilisi a centre in which to build an opposition, across the border.

Free Expression

Tbilisi has become more than a haven for Maria and her compatriots: coworking spaces, clubs and pubs scattered throughout the city centre host meetings where new political horizons are discussed and initiatives to support alternative information campaigns are promoted.

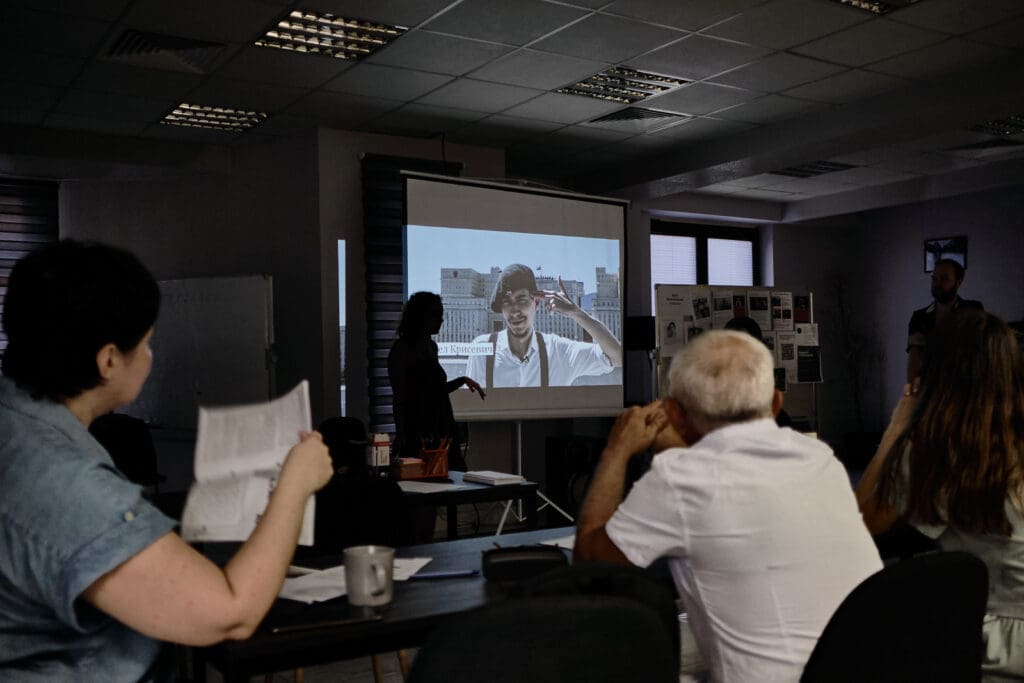

Just as Denis, a freelance journalist and former promoter of Navalny’s political campaigns, did when he was still living in St. Petersburg. “Thanks to the support of organizations aimed at upholding human rights, I found a safe way to cross the Russian borders,” he says, “I reached Kazakhstan where I was rejected; however, then to Armenia, today to Georgia, tomorrow who knows,” he tells me as he sets up preparations for the next event. The hall fills with his fellow citizens with different stories united by the same ideals.

“In an ever-changing environment, dialogue is crucial,” he explains. “It is not easy to build, but I believe that strengthening communication with those still in Russia could be one of the possible solutions to deal with a situation inside the country that is becoming, day by day, more intricate and worrisome.”

Prominent among the initiatives are testimonies by former prisoners: events in which young girls and boys who reach Georgia share their experiences of nonviolent protest followed by arrest and detention. The lights go out, silence falls, and I sense an aura of concern and uncertainty, partly due to my presence. “You’re welcome,” Alexej, a young activist who, along with Denis, was in charge of organizing the event, tells me. “And you can take pictures of Denis and me, but please don’t frame the faces of the other people present.”

Although Georgia remains a haven for many, in recent times, the perception of safety seems to have diminished. “Since our arrival rumors have been circulating that there are Russian agents intent on monitoring our initiatives.[6]” Alexej confides to me, confirming growing concerns.

Following the discussion, participants are given space to write letters to political prisoners still held in Russia. “In drafting, we have to be very careful to avoid censorship,” Denis explains as he sketches a drawing of a small bear on the letter, “even a simple sketch, with no apparent meaning, can convey a glimmer of hope.”

Russian soul

It is a much deeper issue than how it is told,” Leda explains to me in the dimness of her room as she hands me a steaming cup of Turkish coffee. “While many people have a passive attitude toward government policies, it is objectively difficult to protest in the face of facts due to increasingly timely and stringent censorship.”

A Russian activist known among dissidents for her installations in Red Square and on the streets of Moscow, Leda has experienced firsthand what it means to sacrifice one’s freedom for an idea. “The problem is that even today, the predominant attitude consists of statements like ‘Okay, we are against the war,’ but this is not enough and does not translate into concrete actions,” he confesses to me. “We must take action and put our safety on the back burner.”

A thought widely shared by most Russians living in Tbilisi and manifested through promoting solidarity initiatives. Many arise from the common feeling of providing a contribution to all those who, because of the ongoing conflict, have lost a home, loved ones and the prospect of a future.

Support comes in different forms, as in the case of the Itaka Books bookstore, a place that was the brainchild of Stas Gaivaronsky with the intention of offering Russian-language books in exchange for Ukrainian refugees.

“Stav is the owner of the bookstore, but in recent months he is no longer here,” a young Russian girl who runs the store shyly tells me. “We first came here in 2017, and after a short walk through the city streets, we immediately fell in love with it. Given recent events, we intend to stay and provide support as we can.”

For many Russians, staying in Georgia means taking action, free from government oppression, in support of those who, like them, have had to leave their homes. “We counter war with humanity,” Katia, a young Russian woman who decided to move to Tbilisi permanently to provide support to Ukrainian refugees at Volunteer Tbilisi.

“Here I have found a new family, which allows me to oppose this conflict and lend a concrete hand to those who have lost everything to the war,” she confides, proudly showing me the work she, and many other boys and girls do every day to support Ukrainian families. “We try to provide three hundred and sixty degrees of assistance: we distribute food, medicine and personal hygiene items to families reaching Georgia.”

And the need for help is immense and essential to build a bridge with the rest of the citizens still in Russia. “Our funds mostly come from Russia, and over the past few months we have noticed an inflection in donations, partly as a result of the impoverishment caused by European sanctions,” explains Daniel, a volunteer with Emigration for Action, an organization born out of the desire of Russian emigrants to help Ukrainians in need. “In this way, even citizens who used to support us from within Russia are now finding it difficult to give to charity, unable to sustain a steady flow of donations.” Daniel looks up. “This means we will have to find alternative systems to raise funds, as the conflict is still ongoing, and until then, people will not stop coming.” Daniel looks up at me and smiles, “And we will continue to help them as long as we can.”