The only way to access the hulls is via narrow, very flexible walkways that connect the banks to the river. On them, one must advance slowly, one step in line after another, being prudent not to lose one’s balance. As I attempt to get on several boats, I notice that people look at me smiling, with a mixture of amusement and concern, almost expecting me to fall into the water at any moment. But as soon as the distance shortens, their faces open to an expression of surprise, immediately giving way to a warm welcome.

Once on board, it is customary to remove one’s shoes, as one would upon entering the home of a close friend, as a sign of respect and gratitude. When barefoot, one feels more comfortable on rough wooden surfaces, which offer a secure grip on contact with the skin, than rubber soles. A few people live on each boat: a man, a woman or young families with whom, though speechless, one quickly understands each other. All it takes is a nod to be welcomed and invited to share a simple meal, accompanied by smiles and glances that create immediate mutual trust.

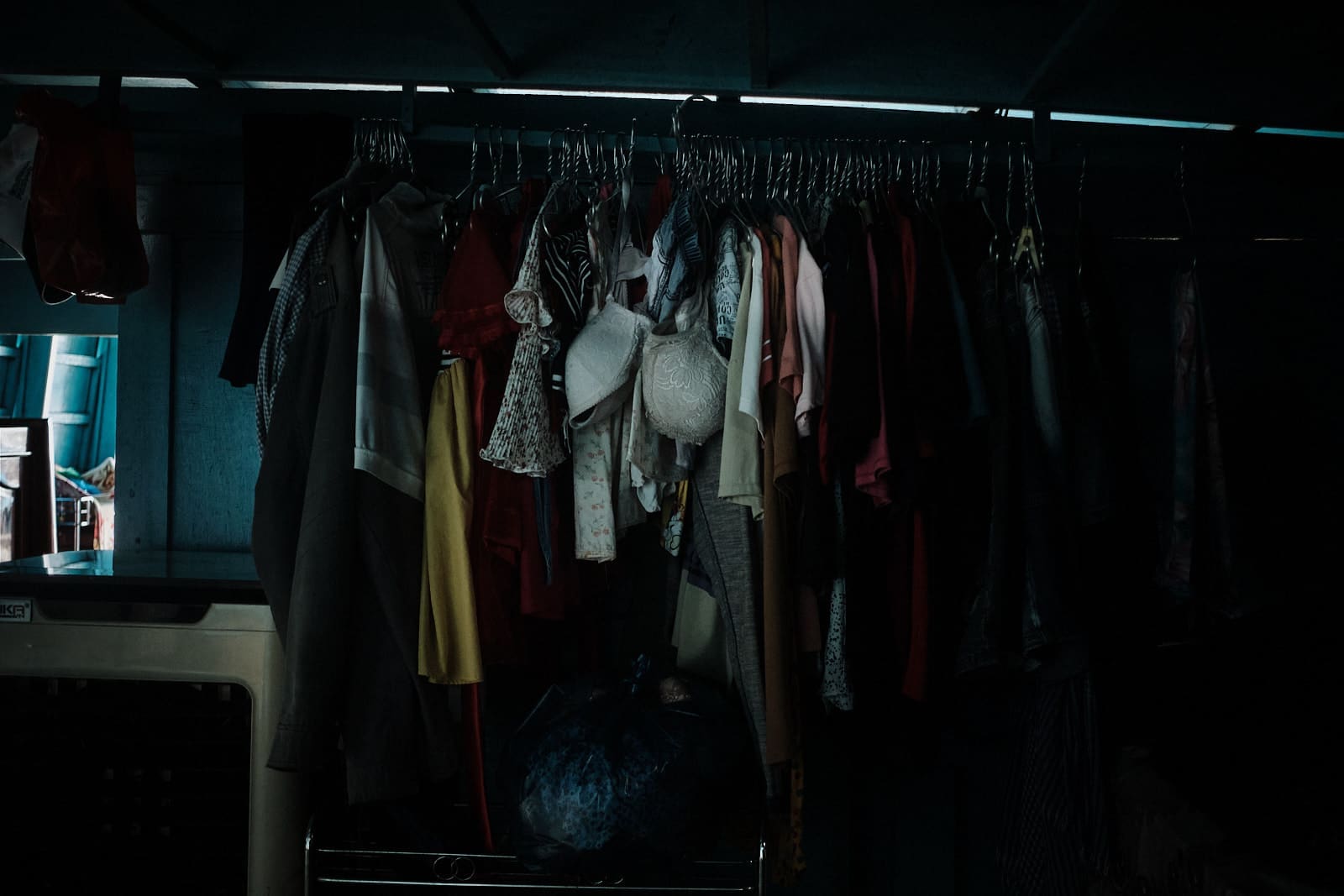

Getting on a boat is always a fascinating experience, but it has a unique meaning here, along the Mekong Delta. Being welcomed aboard in cabins veiled in brightly coloured fabrics conveys the feeling of entering a space that, for those who live there, can represent everything: a refuge, a job, a home. An entire existence gathered in an essential space to feel welcome and safe. Each boat is unique, custom-built for its owners, and united by the eyes painted on the bow, an ancient tradition that has protected sailors from river spirits over the centuries. Larger hulls often carry construction materials, such as sand and bricks, essential for work along the banks. In contrast, smaller ones carry fresh food and handicrafts destined for sale in traditional floating markets. Thus, from east to west, boats cross borders drawn by the Mekong, carrying goods from neighbouring countries such as Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

Moving around the boat, from the cabin to the hold to the small closets intended for the most intimate spaces, such as those dedicated to prayer, one finds oneself immersed in a small universe, which seems to require the same care and attention as a living being. It is an intimate space where one lives in harmony with the slow and gentle flow of the Mekong, led by an exposed and light life, lived with an extraordinary normality. It is an existence that is to be welcomed as it is, allowing itself to be rocked and knowing how to listen to those silent beats that only those who are in the rhythm of a current can catch: a sudden breeze that announces a storm, or a grating that recalls ordinary maintenance.

A floating life, a master of delicacy and tenacity, and perhaps for that very reason so profoundly worth living.