I retrace that road in my mind: arid, dry, where the wind blows hot air, thirst dries the palate, and the sun burns the skin. Animals desperately search for a mudhole to drink. They wander aimlessly, without master, without hope. Here, in the Tierras de los muertos, live the Wayuu people.

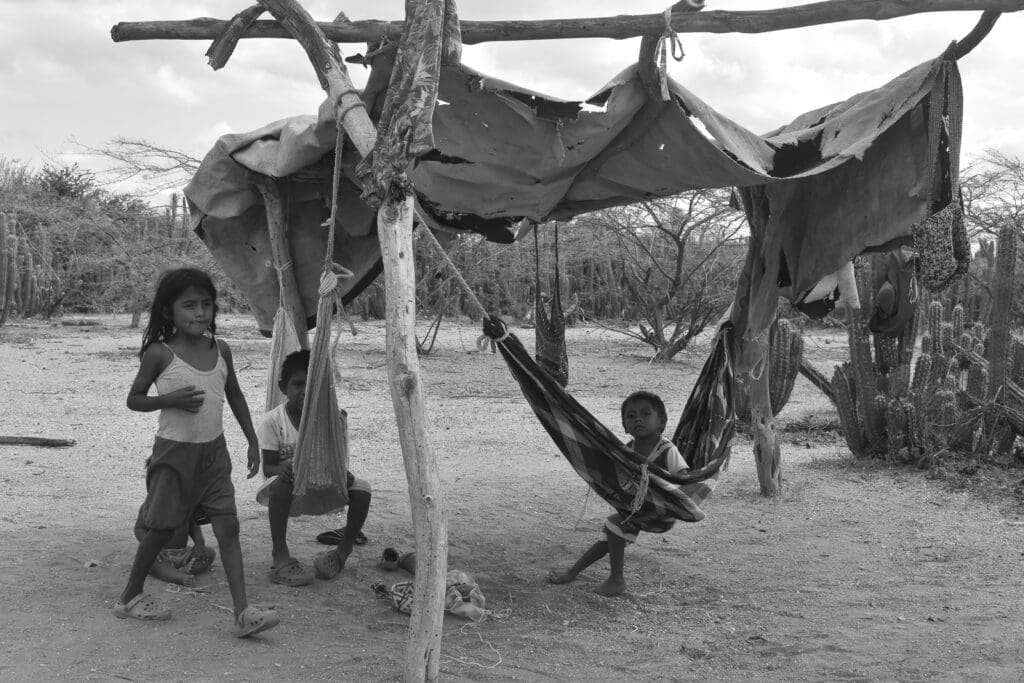

In the land sacred for its stones, the people survive by begging for a sip of water, a piece of bread, a cookie. They run barefoot and wear the same clothes for weeks because water is a luxury, even for drinking, let alone using it to wash.

In the distance, plastic tanks look like mirages in the desert. But they are dirty, like water collected with toil and sweat in scattered wells. In this godforsaken land, the whistle of a train carrying coal resounds. This is the train of industries that have taken over these mineral-rich lands. The jeep runs, the sand blazes in the streets, and only feeble ropes can stop it. These are made-up ropes: they represent the false hope of change that seems not to be happening or, perhaps, for many, they are just the rope of resignation. They are strings steeped in a desperate plea for help to a state that has forgotten this piece of land. They are fragile, like the hands of the one on the other side of the rope, holding together a thread tied to a tree branch, a den of what will be the loot at the end of the evening.

Wayuu, the children of the Sun and Moon

Having survived the barbarities of Spanish colonisation, the Wayuu people have found favourable conditions to develop their economy based on fishing and pastoralism in the arid and impassable territory of La Guajira. The Wayuu are the custodians of an ancestral culture, and their name is synonymous with the human being who, through dreaming, connects his soul with Mother Earth: Maleiwa.

In the funeral cycle, one of the most essential rituals in Wayuu society, the culture reflects the concept of the link between life and death, the importance of transit and the transformation of the soul. It is believed that when a clan or caste member dies, their spirit will travel to Gepirra (Cabo de la Vela), and their soul will go to the sea, ready to begin the journey to the otherworld.

The Wayuu funeral ritual is divided into two stages corresponding to death in two stages. Physical death as the separation of the spirit from the body and, then, the “second death,” when the soul finally disappears into oblivion, when no one remembers that person anymore. Although the second funeral and oblivion do not coincide temporally, they share a significant social meaning: both concern the disappearance of individuality into a collective dimension.

From a social perspective, funeral rituals have crucial significance, with the family called upon to demonstrate generosity, hospitality and friendship toward the community. After two to ten years, the second funeral takes place. The bones are exhumed, washed, and, after a nine-night vigil attended only by the immediate family, are transferred to the matrilineal clan cemetery. This place assumes fundamental importance, symbolising the link between the clan and the territory, attesting to its ownership.

The Wayuu people are divided into castes or clans. The role of women is crucial. This defines them as a matrilineal society in which women’s prestige is closely linked to procreation, giving them the power to ensure continuity and permanence to life and having the right of the bloodline over their children. Another well-known ritual is that of theentierro, the initiation of girls into adult life, which begins at their first menstruation. During a year of solitude, the girl learns the art of hand weaving, manifesting life desires and feelings through cultural symbolism. Her face is painted when deemed ready to mark the transition to adult female status.

The family introduces the girl by holding a party, where suitors can make their demands, but only the maternal uncle can decide the girl’s fate. The palabrero (pütchipü), recognised by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity, is a mediator charged with resolving disputes with a message of peace, neutrality and harmony in society.

The coal enterprise

Mining activities have always generated negative impacts on the environment and local communities. Colombia, the leading coal producer in Latin America and fifth in the world in exports, highlights a context in which foreign multinationals profit while native peoples suffer severe consequences.

Guajira, rich in mineral and energy resources, has become a battleground between economic interests and environmental sustainability. The mining industry, developed since the 1970s, led to policy changes under the presidencies of Uribe Vélez and Santos, favouring the mining-energy model at the expense of local communities.

The department of La Guajira is now grappling with severe water problems. The detour of the Ranchería River to meet the needs of Cerrejón, the world’s largest open-pit coal mine, has left the region’s residents with less than a litre of water per day while the mine uses vast amounts of water for its operations. This scenario highlights the inequalities between multinational corporations’ profits and the harsh reality of local communities being forced to live with insufficient water resources and no drinking water.

An open-air dump

Guajira is the only region in all of South America where children are still dying of hunger and thirst. Because the government and international organisations have never found an effective solution to this problem, which has been known for years, tourism businesses have taken over, creating new and unhealthy habits in local people and damaging the surrounding environment.

Mountains of all kinds of garbage are found along the road due to the constant passing of tourist vehicles. The government has no waste disposal system, resulting in everything tourists donate, thinking they are doing good, generating a negative impact. Not only does this fuel the already notorious practice of begging by children, who often drop out of school to engage in this activity, but it also contributes to the lack of environmentally sustainable education towards the environment. If there is no concrete initiative on the part of the state, Guajira risks becoming an open-air dump in no time.