On the brink of extinction

Sand, sand and even more sand. The gaze tries to go beyond the line that separates the sky from the earth, searching for men and women, in one of the most challenging territories for survival. The blazing sun does not spare a single square centimetre of this land. In the Colombian Caribbean region, the Guajira desert is one of those places that does not yet appear on Google Maps. Yet for more than ten thousand years, in the peripheral and marginal areas between Colombia and Venezuela, the Wayuu indigenous tribe, or guajiros, has survived. They are one of the last ten Indian-American communities, which today, assailed by hunger, is experiencing a phase of progressive extinction amid institutional indifference.

A coveted land

“Bullets were flying in all directions, coming in through the windows. Then there was that cry for help that suddenly broke the deafening silence that always follows explosions,’ Alvaro José Miranda Leon, a resident of Riohacha, tells me. Facing the balcony, he points to his neighbour’s house. He transported her to the hospital while the woman was bleeding out in the back of his car one night in 1988. “Stray bullets,” he whispers, still lost in the memory of the horror that regularly took place in the streets of his neighbourhood. Those were the Colombian lead years, under the rule of the Bloque Norte of the Auc, responsible for staining the whole department with a trail of blood, tears and terror.

The guajiros are a commmunity who have endured all kinds of violence over the centuries. Land of gold, pearls and enslaved people: this is what Guajira was called in the 16th century, in the days of Nikolaus Federmann and his fellow conquistadors, who – in the name of alleged white supremacy and with the hope of germinating civilisation – began a long war of extermination of the native peoples.

More recently, however, it has been the Colombian drug traffickers and paramilitary squads that have set their eyes on the Guajiro territory and the lucrative profit guaranteed by its strategic location: on the one hand, immediate access to the Caribbean Sea, on the other, the border with Venezuela. With only one problem: an enemy that is not easy to beat. The Wayuu, a warrior people, hardened by several attempts at colonisation, organised a solid resistance. Shortly, the murder rate in the area skyrocketed to an all-time high: 442 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants.

Alvaro is my guide in indigenous territory. He accompanies me into the guajira land along a route with a gruesome name, ‘la caravana de la muerte’, the same road that Venezuelan petrol smugglers take every night, making their way through the acrid smell of the carcasses of giant trucks bursting in the darkness. Even now, the narcos’ merchant ships can be seen off the coast, watched by the attentive eyes of some Wayuu fishermen, the Apaalanchi.

Land and Water

In fishing, the heartrending cries of ravenous seagulls and fish gasping in the sand frame an alternation of life and death, an ecosystem that has barely survived thanks to the collaboration of each link that makes it up, and which is now, unfortunately, suffering the consequences of profound contamination of the land. The Guajiros have tried to perfect their procurement technique for centuries. However, it is still characterized by small wooden boats and trawling. Shoeless and equipped with large nets, they wade into the lagoon’s shallow waters, dragging their feet to avoid being stung by the giant manta rays camouflaged in the seabed. The murky water envelops them. Only their experience guides them toward their prey, as if following the steps of a traditional dance, they gracefully launch their lethal trap into the brackish waters of the lagoon.

Land and water are the elements that encapsulate the principle of creation, harmony and fertility: life and origin. The woman represents the earth, while the man is like rain, with the task of penetrating the soil to make it fertile. But the rain rarely falls here, and multinationals in the mining sector have contaminated the few water sources. Heading inland, an hour away from the eastern seacoast, is in fact the main cause of the ongoing humanitarian crisis against the indigenous people: El Cerrejón, the world’s largest open-pit coal mine.

In this area, Human Rights Watch reports, the infant mortality rate is five times higher than in the rest of the country, affecting 27.9 percent of children under five years of age. From this region comes 44.4% of the country’s coal exports, handled by three mining giants: Anglo American, BHP Billiton and Glencore Xstrata. The State facilitated the exploitation of the land, considering it necessary for the economic development of the area. Result: environmental devastation, water injustice and violation of human rights.

For the Alijuna – as the outsiders, the non-Wayuu are called by the natives – it is impossible to fully understand what the destructive manipulation of the territory means. Above all, it is impossible to understand people who identify with every element of nature and live in an ancestral connection with these spaces. Each grain of sand that sticks to the skin, carried by the indomitable desert wind, holds the spirit and soul of an ancestor.

A matriarchal culture

Together with Alvaro, we enter the Rancheria Piulaka, the territory of the Epinayu clan, in the middle of Guajira. Tiny houses built with clay and pieces of wood are scattered here and there. The wealthier ones have a concrete facade and usually goats in the courtyard, status symbols of wealth. One of the elders, lying in a hammock woven probably by the slender hands of some village woman, recounts some creation myths. The sun, the rain, the earth, the darkness, and the wind are the natural elements that created, in their likeness, the Guajiros people.

Wayuu culture is based on a matriarchal social structure. The importance of women is linked to their role in bringing up children, maintaining clan cohesion and promoting peaceful solutions to conflicts. It is through certain rituals, such as the páülüjüt, that, at their first menstruation, young women are confined to their homes for a minimum of twelve moons, so that they can build their female identity thanks to the teachings passed on by their elders. Respect, responsibility, honesty and love are the fundamental values to becoming the future moral leader of the clan. Weakening the woman means breaking the backbone that supports the people, thus destabilising the strength of the indigenous resistance. This is something that those who seek to bend the Guajiro people have learned well, so much so that the victims of violence by Colombian criminals are often women.

Women are also the guardians of the rituality linked to the art of weaving, a sacred form of writing that captures the oral tradition. Weaving means going back to the origins, intertwining the threads of the world and showing the structure of the cosmos. The textile artefacts of the Guajire women – above all colourful handcrafted bags – can also be found on the sidewalks of the Riohacha seafront, as well as on the catwalks of Paris and New York. Despite the latest fashion trend of “made in Guajira” this has not succeeded in relieving the precarious situation of the Wayuu. Actually, it has fueled a black market and yet another attempt at exploitation.

These weaves, protected by Unesco, are bought by Colombian traders at bargain prices: a bag created in four days of non-stop work is bought for less than 25,000 Colombian pesos – EUR 5 – and resold to tourists, in shops in shopping centres or airport boutiques, at costs that are twenty times higher than the initial price. This art, which has become essential for the entire family’s livelihood, is the only source of income to buy the maize flour used to cook chicha and arepas, the primary source of food in the desert but with insufficient nutritional value to cover daily requirements.

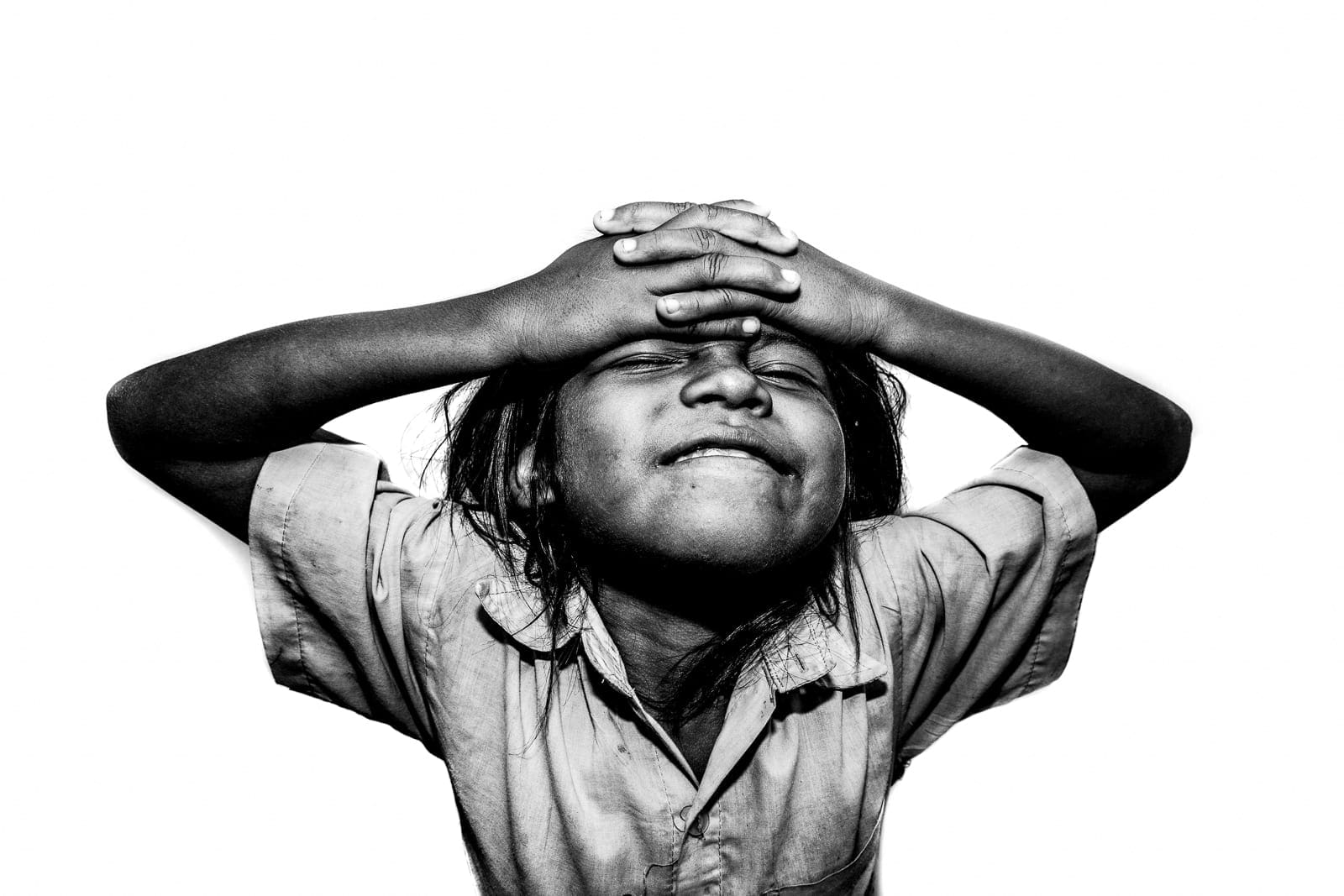

Poverty, dances, spirits

One detail is particularly striking to outsiders who come into contact with the guajiros’ world: here, adults, unlike children, are always eating. This is because, in extreme poverty, the lives of adults are essential to sustain the whole family, while the death of one child does not compromise the survival of the others. The disease is something only the rich can afford. And it is alienating to observe how, to celebrate the funeral of a son who died of malnutrition, a goat that could have been used to feed him is sacrificed.

Indeed, Wayuu culture is linked to ancient ceremonial traditions, such as paying homage to the spirit Alanía, to whom tribute is offered to neutralize evil and protect the deceased.

Spirits and gods permeate every aspect of Wayuu life, and rituals and ceremonies are dedicated to them. Dancing, for example, the mind empties to pay homage to Maleiwa, the creator god. The fertile young women, possessed by the pressing rhythm of the drums, begin to dance gracefully as the sun sets. The Yonna, or Chicamaya, is one of the most sacred expressions of their culture: a succession of passages alluding to the wayuu animals, uchii, ancestral protectors, and nature, the highest manifestation of the divine. The drum beats, generating a rhythm that brings us back to the spiritual essence of life, creating a relationship between the cosmos and humans, and beating Mother Earth’s heartbeat. The dancers’ quivering feet create swirls of sand that sweep over the scene, transforming it into a blurred but vivid enchantment.

Back in the city, the contrast is strong. Instead of the sand of Guajira, the smell of asphalt and food from the kiosks by the sea invades the nostrils. Reggae music, tuned to the sound of the waves, is sung by tourists in swimming costumes who, sipping a tamarind juice, intone ‘One love, one heart’, unaware, or perhaps not, of the existence of that other world that, abandoned, drowns in the desert dunes.