Hairpin bend after hairpin bend, the road plunges into the lunar underbelly of the Lefka Ori and trudges toward the village of Anopolis in a dreamy or nightmarish landscape, depending on your point of view. On one side is the Libyan Sea, whose waters gently lap the foot of the Cretan region of Sfakia. On the other side of the road, however, rises a white framework of stripped rocks that have earned the Lefka Ori –White Mountains– the affectionate nickname of Madàres, meaning “naked.”

Occasionally the silhouette of an olive tree clinging to a rocky ridge appears, but it ends there: the rest is wind, thorny shrubs, pebbles rolling down the slopes to the road and bleats from goats near and far. And vultures, too: Thomas, our guide, pulls over the cliff and points out a few circling in high circles in the pale sky above our heads. They are majestic, solemn animals, perfect for this world of bare stone cut by deserted roads. Then, suddenly, in the stillness of the hot Cretan October, there is the sound of crashing rocks and a terrified, dismayed bleating, which dies away in a sinister thud not far from us. Then it is spectral silence again, broken only by the distant cries of vultures: ‘they have found dinner,’ Thomas comments.

It is not uncommon to find goats smashed on boulders here: the animals climb the vertical walls to reach some thorny bush, but the rock of the Lefka Ori is crumbly, death always close to the hooves. Thomas remains motionless for a moment, contemplating the desolate vastness around us; he puffs out his chest and lets out a proud sigh before getting back into the car: ‘Ah, Sfakia! Then it’s off again to Anopolis, a tiny village of shepherds and farmers embedded like a splinter in the untamed heart of Greece’s largest island.

Rebel valleys

As the car leaves behind the blue of the sea and the white of the bare rocks, a splendid verdant plateau suddenly opens up in front of the windshield, embraced by a crown of mountains: rows of silver olive trees slope down from the slopes to the village, between fences, dry stone walls and low houses. From time to time a lopsided sign indicates the presence of a few studios (apartments for rent) or “rooms to let” not far away, among the vegetable gardens: more often, to be noticed are large black pickup trucks parked next to tractors, the flatbeds occupied by filthy cans or large, scowling-eyed shepherd dogs.

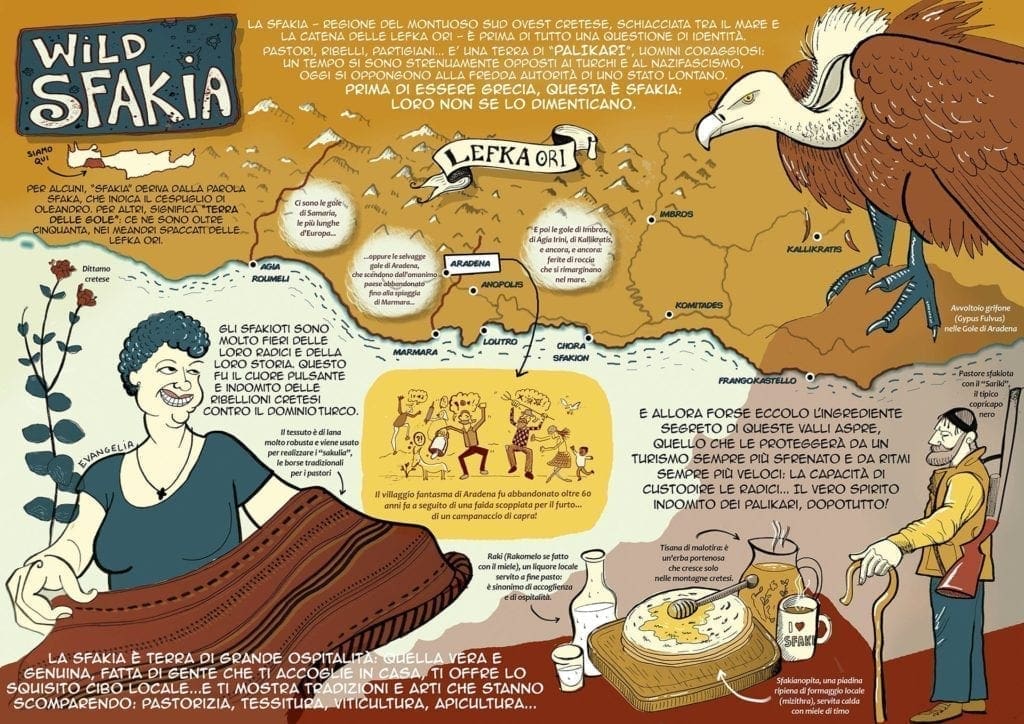

The bucolic gentleness of the village of Anopolis is only apparent: the material of which the town is made is the same complex and rugged as the Madàres surrounding it. This is a land of shepherds and bandits, of andàrtes (partisans) and rebels that not even Turkish rule over the island has ever managed to bend, let alone Athens or the EU; it is a land of graceless life and powerful roots, identity and pride. It was in this very village that Ioannis Vlachos, the national hero known as Daskalogiannis, was born. In 1770, he led the first Cretan revolt against Ottoman rule: he paid with his life, the village with a fierce retaliation that razed it to the ground, but the proud spirit of that revolt still permeates these valleys, and a bit of tourist make-up is not enough to conceal it.

Proof of this are the bullet-riddled road signs, the goat skulls hanging from fences and the proud frown of the men, clear eyes in sunburned faces and strictly black clothing, some with dark sariki (the traditional scarf, fringed to symbolize tears) wrapped around their heads. “Before you are Greek, you are Cretan,” Thomas explains, “and here, before you are Cretan, you are sfakioti. And being Sphakiotes, we discover, means above all honoring one’s roots: not easy, when more and more glossy brochures propose “wild Sfakia” as a tourist attraction, radically changing the face of an area that has remained unchanged for centuries and turning traditions-food, village festivals, handicrafts-into low-budget entertainment, exquisite local hospitality into a postcard stereotype.

Red for blood, black for pain

For us, Sfakiota hospitality has the round, lively face of Evangelìa Kopasi, who opens the doors of her home to us and embraces us as if she has known us forever, talks in Greek with Thomas, and then disappears into the kitchen to reemerge with her arms laden with every blessing: plates of local pancakes, like sfakianopite stuffed with mizithra (soft goat cheese) and covered with thyme honey and kalitsounia stuffed with herbs, cups of steaming Greek coffee, saucers of must cooked with sugar and sesame… The courtyard, under the arbor of strawberry grapes, is a party: “Parakaló! For you, guests!”

She wants to narrate, Evangelìa. We have come to her to discover the traditions of the Cretan hinterland, but we realise that what we are looking for within a few years risks being a ghost: ‘this is our world, and we see it disappearing,’ she explains. ‘We know that it is an unstoppable process, that we cannot stop time passing. However, it is painful’. Evangelìa is 54 years old and was born and raised in Anopolis. Together with her elderly aunt Vangelio, she is one of the few local women still capable of working the traditional Sphakiota loom and spinning the fabrics that guard the identity of the Anopolis plateau. Commencing with the colours: red for spilt blood and black for pain, together tell the story of life and death in this harsh and demanding land.

“With these cloths,” Evangelìa explains, ” sakulia, the large bags used by shepherds when they go up to the madare, the sheepfolds in the mountains, are prepared: they are used to carry tools, food, even lambs and cheese returning from transhumance. Only a few years ago, red and black sakulia were routinely used by the people of Anopolis as wedding gifts, along with tablecloths and towels always made on a loom and finely embroidered by hand: they were slow and refined preparations, but also occasions for sociability and meeting among the women of the village.

“The men met in the kafénio to talk politics, we in the courtyards to weave and work at the loom. Each family had its own, passed down from woman to woman. Ours, you see, my aunt Vangelio inherited it 60 years ago from her grandmother, who had already been using it for decades’. So the enormous wooden structure bears time signs: the ruined pieces have been fixed with makeshift replacements, such as curtain rods or tomato stakes, and tied together with rags or ropes. Evangelìa keeps it in the courtyard under the pergola and weaves the rough red and black wool morning and afternoon: she is fast and precise, in her hands the skill of someone who has been doing that work since she was a child. At the same time, she tosses the shuttle between the threads and knots the traditional embroideries. Her aunt sews and helps her weave the sakulia ties tightly.

There is a veil of bitterness in the eyes of the two women: they know very well that when they are gone, there will be no one left to preserve and pass on this tradition. “The girls are not interested in learning,’ Evangelìa explains. ‘It’s not worth it: it takes too long, and they are not products with a significant market today… They have value for us, but for those who pass through here on holiday, they cost too much and mean nothing. They say they can find them equally and cheaper in souvenir shops. Equal… Whatever.

Deep roots

The elderly Vangelio shares with her granddaughter the sadness of those who see the shadow of their world stretching over the present. Born 85 years ago in the tiny fishing village of Loutro and having moved to Anopolis after her marriage, she has seen her home village slowly depopulate, the houses of the inhabitants give way to small hotels and restaurants, the fishermen and shepherds give way to German, English and Italian tourists: ‘these villages now only live in the summer. Before, they were inhabited all year round: today, when the summer season ends, everything dies. Nobody lives in Loutro in winter any more’.

European Union policies do not always help: the crisis has hit less hard here than elsewhere in Greece, and the signs of austerity are more subtle, but EU funds are granted only for a few specific rural interventions, and those who invest in the area do so at the expense of the area’s traditional crops, such as vines, or exclusively with a view to tourism enhancement.

“There is not much we can do,” Evangel continues. “Tourism is undeniably a resource, especially for young people, if done with respect. But our traditions, like this, are in danger of disappearing-they are already disappearing. And what will be left then? When do people look for other vacation destinations when EU funds for “rural redevelopment” cease? What will be left of us then if we have lost everything?”

For this reason, the two women do not want to change the embroideries on their yarns or introduce new designs: “It is not a matter of personal whim or fancy. These decorations and colours have meaning and value: they reveal who we are and where we come from. It is our identity; we cannot and will not change it. What are we without our roots?”