The Russians? – Niko scratches his shaggy beard, then his bright eyes light up with understanding in his tanned face – Street, street! – and points with one arm to the sun-bleached strip of asphalt that unfurls just beyond the dusty courtyard, where chickens, turkeys, a horse, two dogs on the chain and several goat skulls hanging to dry in the sun.

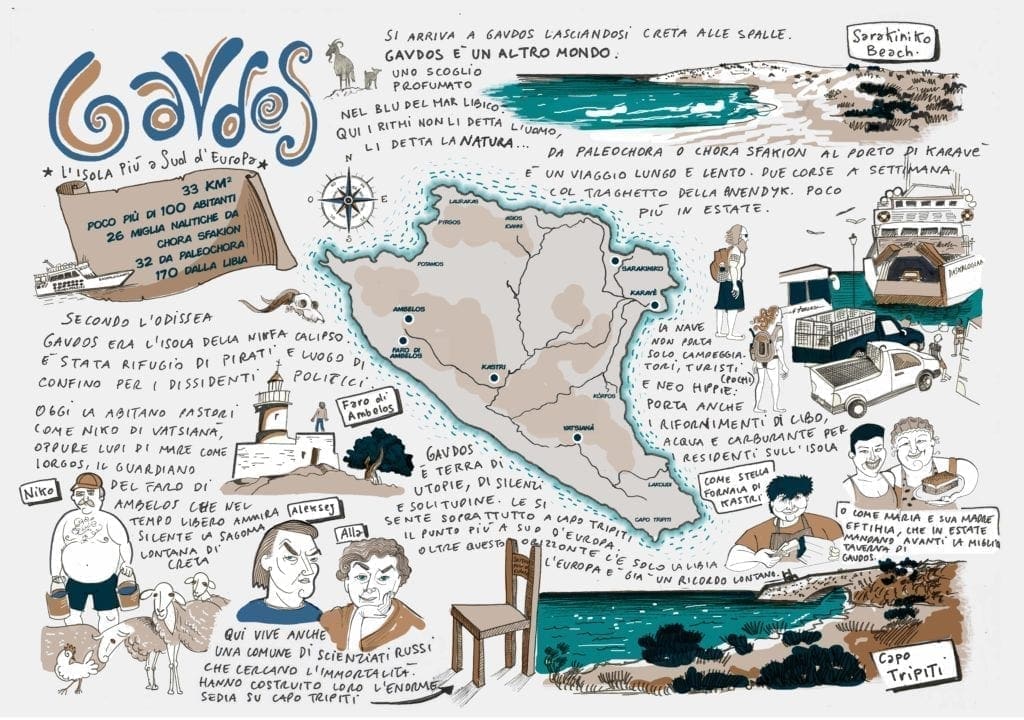

The Tripiti Café is the most southerly kafènio in Europe and probably the shabbiest. We are on the island of Gavdos, 37 square kilometres forgotten by the gods between the Cretan and Libyan coasts: here, the summer hardly lets up, the stillness is that of myth, and the silence too, interrupted only by the bleating of goats and the rustle of the wind that is laden with aromas among the juniper and savoury bushes.

Shepherd, manager of the Tripiti Café, historical memory of the island and father of three of the four children who attend its tiny school, Niko is one of the few inhabitants of Vatsianà, the southernmost settlement on the European continent. He is the one who pointed us to our destination, the reason why we got lost in the undulating paths of this emerald green island and why we ended up in his kafènio in search of information: the house of the Russians, a little further down the road.

The Gavdos Immortals’ commune.

Scientists and philosophers

We have to wait about ten minutes: Aleksej Yuzgin arrives in a cloud of dust in a rickety pickup truck that stops with a sinister screech in the front yard. He nods to us and takes off his work hat. Immediately we recognise his Slavic features, his sharp face, his intense, aquiline eyes: «Are you here for the interview? – his English is tinged with Russian, sometimes words in his mother tongue escape him – Molodèz, good, come, have a seat». He seats us in a smoky lounge stuffed with work tools, ethnic decorations, books and papers. Alla Yavtushenko, a middle-aged lady with blond hair, greets us, exchanges a few words with Aleksej and then sits with us, lighting the first of many cigarettes. «Well –he smiled– what do you want to know?».

Rumours about the group of people originating from Russia and living on the island of Gavdos abound; we collected several before arriving here. On the island everyone knows them; to everyone they are simply “the Russians.”

They say they came here after Chernobyl to detoxify from radiation. They say they belong to some esoteric sect. They say they are building a temple dedicated to Apollo. They say they are scientists, philosophers, scholars, people who wanted to radically change their way of life out of the logic of capitalism to seek in ancient Pythagorean philosophy the principles of immortality and build a new society. They say they belong to some esoteric sect. They say they are building a temple dedicated to Apollo. They say they are scientists, philosophers, scholars, and people who wanted to radically change their way of life away from the logic of capitalism to seek in ancient Pythagorean philosophy the principles of immortality and build a new society.

So, when we ask Alla and Aleksej what is true and what is not, they grin to the side. Because, in a way, it is all true, and there is nothing secret about it. At least officially.

From Chernobyl to Gavdos

Chernobyl, for example, really has something to do with the story of this small group of scientists who decided to leave Russia and move here. «It all started with Andrej Drozdov –explains Aleksej–. He had been one of the voluntary liquidators immediately after the nuclear disaster at the plant and had been exposed to a deadly dose of radiation. A doctor gave him some pills to treat himself and the address of a Moscow clinic, but he knew it wouldn’t do any good. So he decided to do his own thing: he did not take his medication, went to the countryside and started working hard in the fields, sweating a lot and drinking vodka. To purify his blood. It worked –specifies Aleksej– because he is still alive».

It was in Russia that Andrej began to gather around him people – mainly physicists, engineers and scientists – interested in investigating how the power of the mind could change bodies: their research led them first to delve into Russian philosophy and then back to the ‘base’, Greek and Pythagorean philosophy. And it was during a research trip to Crete in 1997 that an Orthodox priest gave them a few acres of uncultivated, stony land on the remote island of Gavdos, near the semi-abandoned village of Vatsianà.

It is the beginning of the commune: seven people – including Andrei, Aleksej and Alla – move to the island, abandon their academic life and scientific experiments, and begin a new path, made up of laboring, active meditation and back and arm work: over the years they fix roads, churches, paths.

They transport materials where no one else could get to, build houses and repair cars, test their bodies with the most strenuous activities.

In 2000, they paid homage to the island with what has become its symbol, the enormous panoramic wooden chair they placed on the rocks of Cape Tripiti, the southernmost point in Europe. They often work for free, sweat a lot and switch from vodka to raki, the local liquor, while the evenings are devoted to discussions and comparisons, philosophy and research. They established the Pythagorean Institute of Philosophical Studies for the Immortality of Man , and built more houses in Venezuela, Russia and Georgia. There are about 20 people in total, although at the moment, there are only Alla and Aleksej in Gavdos.

«What underlies our research, –Alla explains– is the desire to understand, to experiment, not to limit ourselves to what the books say. Research starts when you have questions: we had many questions and sought answers. We realised that we knew nothing and had to study from the beginning, which is what we do here». We ask about immortality. What immortality is sought here? «Our bodies, –Aleksej continues– have infinite possibilities for change, but we do not use them. We are stuck in lifestyles that block us and prevent development, so we are destined to die. We are already dead people. Immortality is a way of life, one of the possibilities our body gives itself when we free it from the external influences of a sick society».

The Island of the myth

Gavdos is probably the perfect place for such a project, the ideal land to build utopias. Of course, the Russians do it in search of their philosopher’s stone, but so do the many hippies who have found their lost paradise on the island: located 26 nautical miles from the Cretan coast and 170 from the Libyan coast, Gavdos is perhaps the only Greek island that openly tolerates free camping.

On the long, wild, sandy beaches, sun-bleached cedars stretch out dry branches and create ravines, sheltering tents and improvised lounges under the stars. According to mythology, this was the island of Ogygia, home of the nymph Calypso who, to keep Ulysses with her, offered him immortality as a gift. He refused her. Today, the Russians search for it day after day.

Whether they have found it or not, we do not know: and when we say goodbye to them on our way back, when their house disappears around the bend, we are left with the feeling that we have walked for a few moments on the thin border that here, on this abandoned island, separates myth and reality.