Jack’s mission

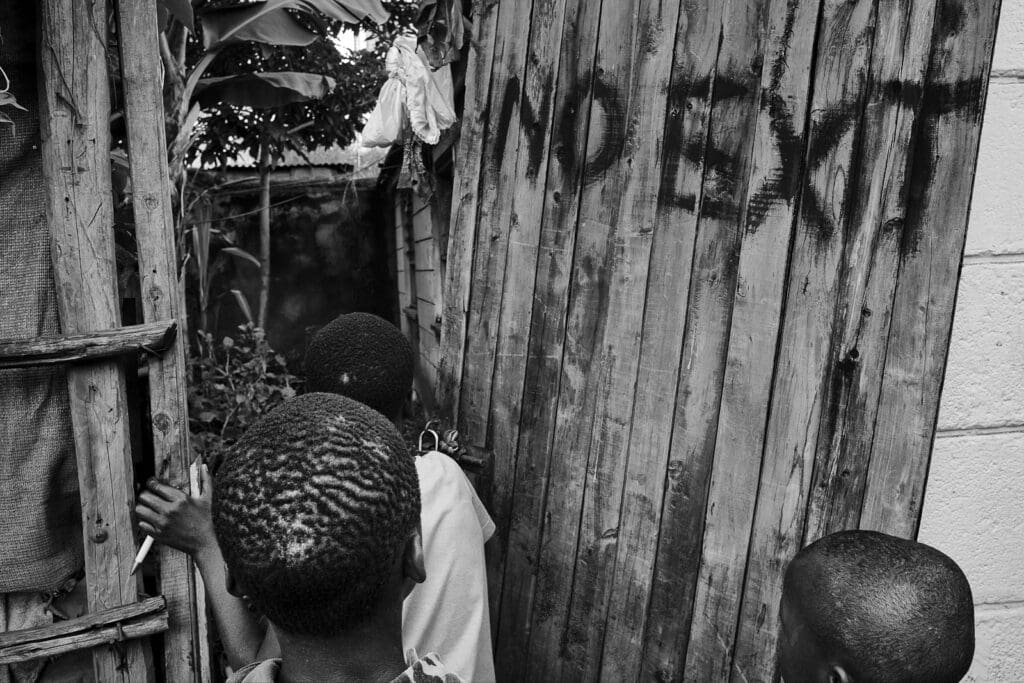

The sun beats relentlessly on the railroad, and step by step their eyes cross with those of many, many other people: the most puzzled adults, the children full of curiosity. I am signalled not to stop as we move through narrow spaces, obscured by the fumes of burning plastics and tyres nearby. Walls of sheet metal and earth outline the road until, almost without realizing it, the view opens up, and the view is dizzying from the dam.

“Let’s go downstairs,” offers Jack, with the confidence of someone who feels at home. He says those born in Kibera are unlikely to leave it, some for lack of alternatives, others to stay and help the community. His choice was similar, when still 18 years old he decided to leave his village and move to Kibera, one of Nairobi’s largest informal settlements, where more than half a million people survive in extreme poverty.

During his years in Nairobi, he became deeply immersed in the life of the suburbs and, on these streets, realized that he had both the skills and the passion necessary to devote himself to social education. An endowment that soon takes the form of a mission: to support homeless families and convince children to leave the street life. In return, he offers them an alternative path of school, dreams, and family. A family built on unconditional love and the caring attention of those you trust.

Shadows in Nairobi

“The families are mostly young, often consisting of only women with their children. They are shadows in the eyes of society, like coins dropped on the ground, considered of too little value to be collected“, Jack tells me as we enter Tsunami, a tangle of alleys and chaotic streets located in an area close to the city centre, where 4,000 families live homeless. Our arrival does not go unnoticed and those who can approach in search of help. Wrapped in a crowd of teenagers, Jack points me to a woman in the distance, squatting near a water channel. “For the past month, we have been trying to track down his son., – and continues – it happens that young people and adolescents abandon their families, most often because of fear of their families, an aspect that can also lead them to extreme gestures”.

The perception of street children by their families is complex and contradictory: on the one hand, a sense of affection and protection for their children emerges; on the other, the difficulty in accepting or acknowledging the reasons that led them to move away. “One of the main reasons is marginalization, both suffered and felt, in times of hunger, illness and violence, which pushes children toward substance abuse,” Jack explains to me, ” a way out often adopted to escape from the bitter reality that surrounds them, and this happens especially in the most vulnerable families.

Substances include glue, gasoline and other spent fuels that interfere with brain development and cause permanent lung damage. A trend that exacerbates an already existing health crisis, highlighted by a rate of infant mortality about two and a half times higher here in Nairobi’s suburbs than in the rest of the city.

The phenomenon is closely related to extreme poverty-induced trauma, which significantly impairs children’s mental health. Jack and the educators of the Koinonia community work daily to counter this trend through the consolidation of twenty-six operational centres located within areas such as Tsunami. Their constant presence is essential to receive in return the listening of children and adolescents, who have given up their dreams to avoid suffering.

Little Brother

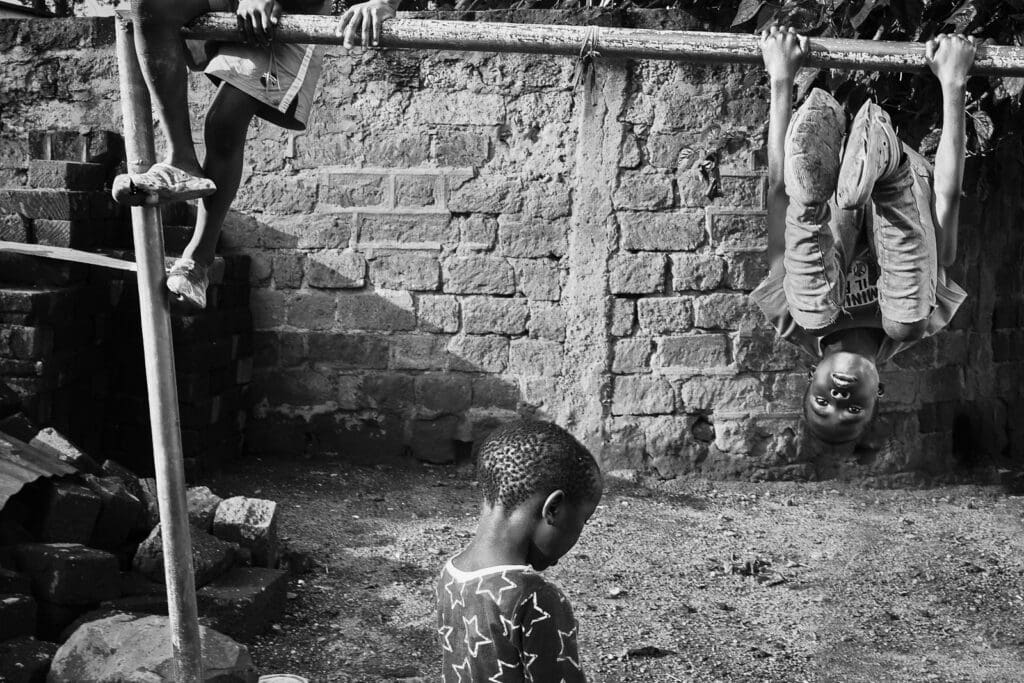

Hands clasped around a railing and bare feet firmly on the ground. Suspiciously he pretends not to see me, although my visit seems to be pleasing to him.

The closer I get, the more he stiffens, so I decide to stop, bend down and meet his big black eyes. I smile at him and point to a graffiti beside him that depicts a set of small handprints enclosed in a heart. He also smiles.

“My name is Fabio, what is your name?” I ask, but the question seems to irritate him to the point where he turns and looks in the direction of a large room down the hall. I interpret his gesture as advice and head toward the open door from which laughter and ringing voices come. I cross the hallway when, suddenly, I feel his hand squeeze mine. I squeeze her and together we head for the door.

“What’s your name?” I try to ask him again.

“Diego,” he replies, looking straight across the room.

“Little Brother,” in Swahili. Ndugu Mdogo, is the recovery centre run by Jack, located on the outskirts of Kibera. Through the collaboration of social workers, government agencies and community members, the centre identifies children in family emergencies by offering them shelter and hope for a better future.

Each year the center takes in a total of 40 children from the street, and since the program’s inception in 2005, about 1,000 of them have gone through this journey of growth and then returned to their families. Jack believes that this is the most important aspect of his mission: that children return home with a solid foundation to continue to grow with their families, knowing that they have the tools they need to handle the difficulties they will face.

The next steps will see the introduction of new programs, no longer targeting only children, but also their families. “About 80 per cent of the children we support come from families living in extreme poverty, who lack the necessary tools to support their children,” he continues. ” This is surely the reason why a large number of young people grow up in a context of violence, and helping families means addressing the root of the issue. In this sense, financial support is an essential form of support, but it is not the most important aspect: “Talking and spending time with children is even more valuable than the services we can provide them through donations,” Jack explains to me, ” it is time, affection and attention that are lacking, more than material goods.

The other part of self

“An abusive father or stepmother figure is usually present. These are very difficult childhoods where the first thing you have to offer the child is safety and make them understand that okay: whoever you are, however you arrived, here you are safe, here you are at home, here you are protected“recounts Father Kizito Sesana, a Combonian missionary and Italian journalist. In Nairobi he started the Koinonia community and in Italy he is among the founders of the organizationAmani. On the outskirts of Kivuli, one of Nairobi’s first drop-in centres has opened: theKivuli Center, a place where children and young people living on the streets can find food, safety, and most importantly a feeling of belonging that extends to the whole community.

Indeed, the generosity and welcome offered within these facilities have helped to create a support network that extends to people outside the centre as well, thus promoting the importance of social inclusion, and a return to the family by the children received.

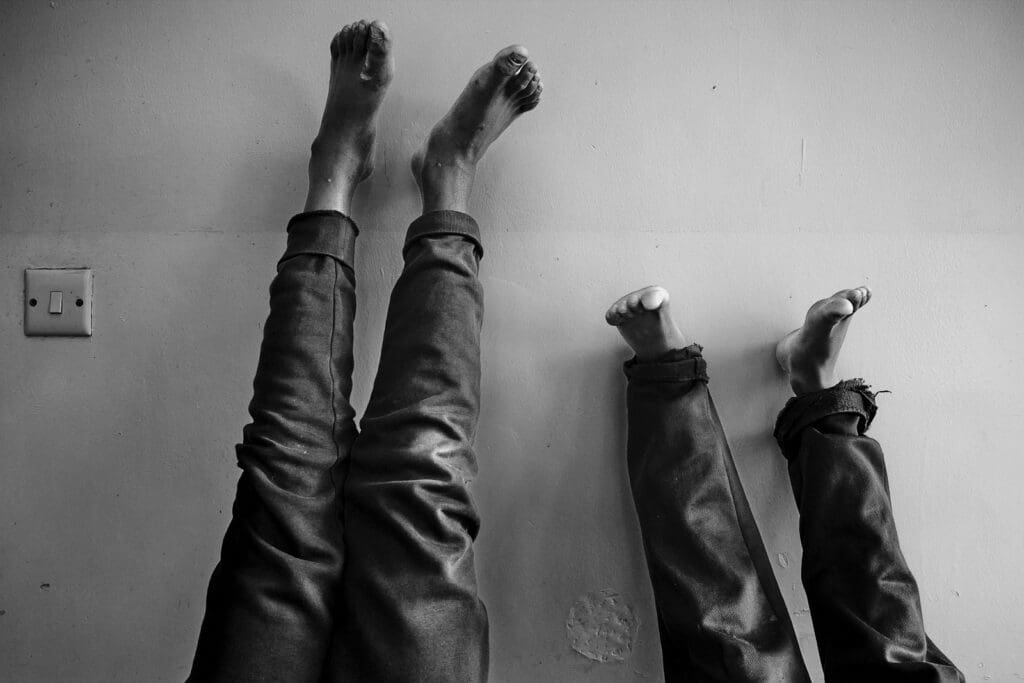

This is a very complex approach that takes time and tries to address their needs, identify the type of trauma and bring out each child’s personality. Some show amazing resilience, managing to overcome intense trauma, while for others the road can be longer and more tortuous. “The road does not cease to fascinate, because it does not impose reflection on them, while in the recovery centre certain rules are imposed,” Father Kizito tells me, ” as time goes by, the experience of some children may prevail over the more fragile part of themselves. A very often denied part of the personality, which they must first discover, then acknowledge, and finally name it.

One must first understand the immense effort required of children, who are called to confront new personality traits, often veiled by traumatic life experiences. “Asking themselves the questions ‘Who am I?’ and ‘Who do I want to become?’ represents the first step toward a path of growth that they must embrace without compulsion,” Father Kizito stresses. For this reason, too, it is crucial to offer them a kind of affection they have never experienced before, an affection capable of awakening a part of themselves, repressed by fears and violence, that only an act of love can release.