Goran was a Serbian paratrooper and died in 1999, in Kosovo, hit during a NATO bombing raid. Jovanka is his mother and she opens the doors of her home in Serbia to tell me how you endure the worst wound: surviving the one you gave birth to. It is a wound that leaves you agonising: you are still breathing but you are helpless.

Bringing me to her is Slavica, an Italian teacher originally from Niš. She is waiting for me at the Ćuprija station with Goran’s best friend and a woman I do not know. All four of us stand in silence with the Serbian countryside flowing past us as Goran’s friend drives slowly toward the destination. She lives alone in a quiet village where she raised her children, where she was a teacher, where she never wanted to leave.

The appointment is in front of the building where she lives but then, almost there, she calls us and changes plans. Slavica explains that she wants to meet us in front of the school where she worked. Now, that school is named after her lost paratrooper. It is in the very courtyard that surrounds the school, a gray building like any other, that the municipality had a bust built depicting Goran.

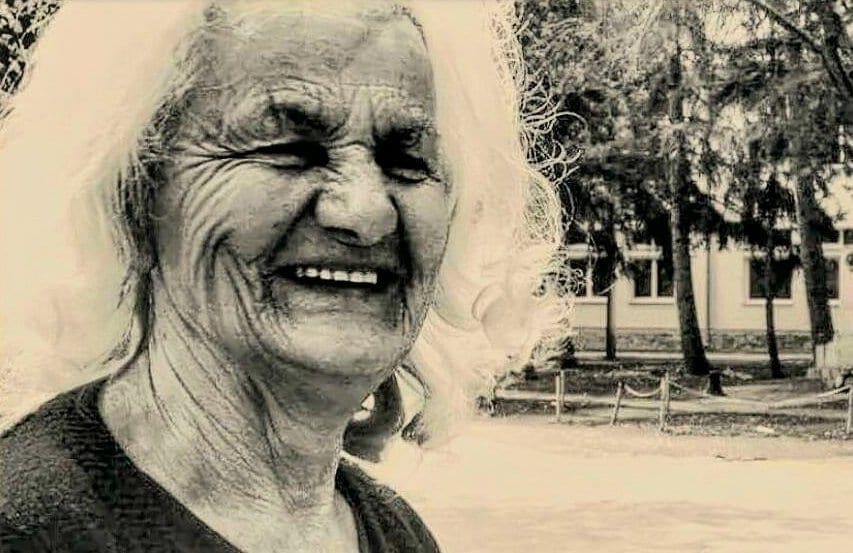

Getting out of the car I see Jovanka for the first time: kneeling in front of her stone Goran. Long white hair, a black skirt and T-shirt, and even her shoes are black.

Slavica calls out to her and she turns and waves to us to come closer. That garden and that statue are her little temple. On her face is a network of deep wrinkles. She caresses me: ‘I spend so much time here, my whole life is here’. He says this with a sadness that no longer feels like sadness, with the peace of someone who has lost and resigned himself.

She suggests I take pictures and, to give her satisfaction, I try to take them from different angles. I feel her gaze on me as I frame Goran’s features and the Cyrillic letters that make up his name. She also wants to show me the street named after him. She holds my hand between hers, thin and stained by old age, and guides me through the streets. She wants me to take photos there too when we arrive: she is proud to see her son’s name around the village. She hopes that no one will forget it even when she is gone.

What do you cling to when grief like this attacks you from behind? Maybe only to memory. The tour is over and we head, a small group in procession, towards Jovanka’s house.

At Jovanka’s house

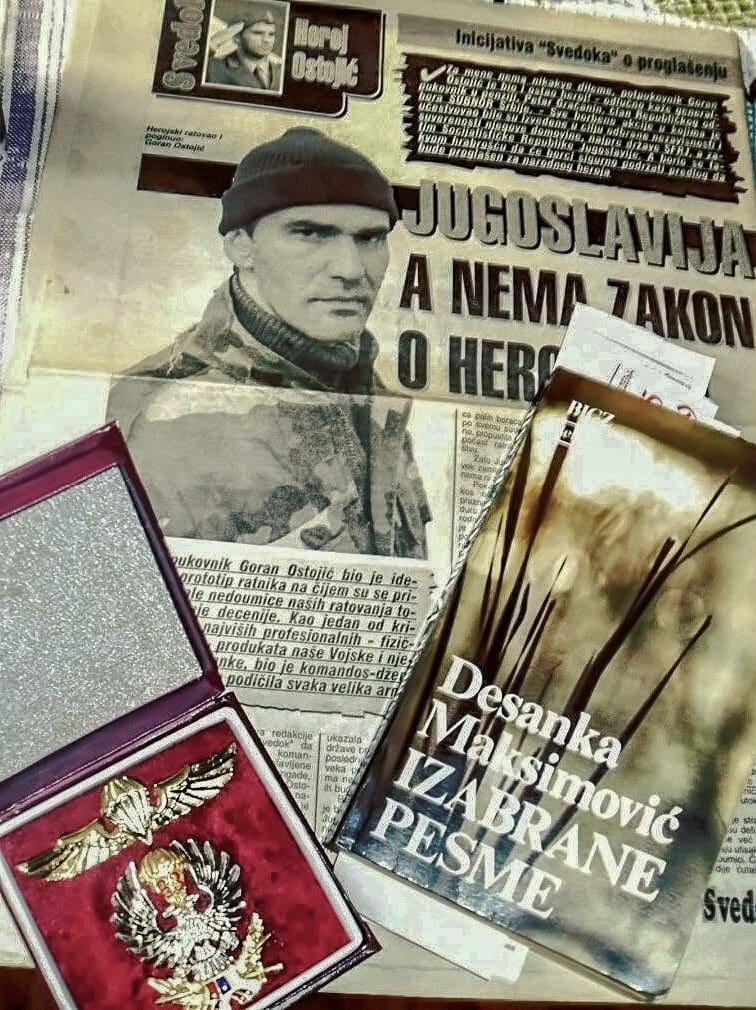

She sits with us in the kitchen. On the walls are photos of Goran as a child and then as a young man. She goes into the bedroom. “I have to get some things.” She returns a little later with a box. She sits down with us and starts pulling out, slowly, photo albums, newspaper clippings in which she talks about her son, the war in Kosovo, and books of poems. One of these books was written by her. Seven years ago, she also won a gold plaque: best poem with a patriotic theme. She brings the plaque closer to me and runs her bony index finger over the engraved words that are the title of her poem.

She brings me a cup of tea and sits down again; I ask her to tell me about Goran, about the man he was. “My son is my poetry. He was a good man; he had many plans. One day there was a demonstration of his brigade in town. Everyone was already lined up when I arrived, a little late. Soldiers have a lot of discipline, but he still turned around and kissed me when he saw me. Then he goes on, back in time to recover memories. He tells me that Goran took his first steps in the garden where his bust now stands: ‘It’s a strange coincidence. “He was a hero; he was there to fight the terrorists; he fought as an officer for eight years”, and I don’t know what to say.

Then she tells me that he, as a commander, never abandoned a soldier. “Never, he was always in the front line. His soldiers were always behind him, never in front.”

My tea and hers have gone cold: she talks to me incessantly and I stare into her eyes as I listen. “To bid me farewell, before an important mission, he would fly over our building in the helicopter from which he would later jump. He flew over this building even before he died. He also passed over to his high school that day. Maybe he had a hunch and waved goodbye to the important places in his life. I wanted to stop him, I didn’t want him to be a soldier, but I couldn’t do anything”. Jovanka’s voice drops and so does my gaze, but we resume immediately.

“He was generous, his soul was not ready for this”. She tells me that he was selfless. He loved his soldiers as deeply as brothers or sons. Goran told her that if she had seen the courage and strength in those young faces, perhaps she would have understood and accepted that choice.

He shakes his head and says, ‘thirty-six’ because thirty-six are the years Goran has lived. He tells me about his passion for animals and rivers. He reads me a poem he wrote for him. It is called The Threshold of Memory, and he read it when they unveiled the bust depicting his son. “They all cried. I tell you, he was my poem’. She recited it on that meadow of first steps she told me about, “where the circle of his existence closed”.

She tells me that she will never accept what happened. It was her brother who recognised the body, and this saved her. She adds that he will never be spoken of as ‘deceased’ because he, in reality, cannot die ‘for how great he was’.

“What does not make me resign is the fact that all this could have been avoided. You can’t make the bad guys better and that’s why I can’t even hate them. Our country, however, did not have to sacrifice its children. It had to take care of them. It was not supposed to allow our children to be killed”.

The time has come to say goodbye; when I get up he asks me to come closer. He takes the box he had placed on the table to show me that it is not empty. He gives me a copy of his book of poems and makes a dedication. “To Rita, with great affection. Jovanka”. He hands it to me and I gratefully place it on my chest, close to my heart. He takes out a parachutist’s hat and a certificate from the box. It has her name on it, it was issued two years ago. She smiles smugly and nods.

She jumped too, from a parachute. She jumped at eighty and wants to do it again in three. She did it for Goran. To understand what she felt when she jumped out of a hatch and flew with no ground under her feet. She did it to feel closer to him. “I can’t hold him anymore, but maybe in the sky we are closer.” Three thousand metres and forty seconds of free flight. “I didn’t expect the impact with the atmosphere to be like this. I was close to Goran and to God.”

A way to avoid drowning

I imagine her, Jovanka, with her flying suit, white hair, and wrinkles cutting her cheeks to face the fear and adrenaline of jumping and two tears falling on the plastic tablecloth.

This elderly woman explains to me like this, with a leap into the void and a green hat on the table, that everyone finds their way not to drown when they think they have no salvation left. She confirms that a mother’s love knows no space, time, or conditions. It exists and will be there until the last of days.

She kisses me on the forehead, says goodbye to the other three, goes down the stairs, and walks us to the car. I turn around, and through the window,w I see her, in her black clothes, standing on the sidewalk watching us drive away, her thin hand raised

Jovanka died a few months after our afternoon together, unable to jump out of a plane again. And I, always terrified by the thought of eternity and reassured instead by the idea of nothingness, on the evening she died I hoped that eternity does exist. And that, in that eternity, all Jovanka in the history of mankind will finally and once again be next to their own Goran.