The tourism boom in Greece, particularly in Athens, is drugging the real estate market. Leaving Greeks homeless. Or forcing them into cramped spaces at the edge of habitability. This is the story of Constantine.

“He wants your soul, and he will try to trap you… To be saved you must see the play to discover the way!“

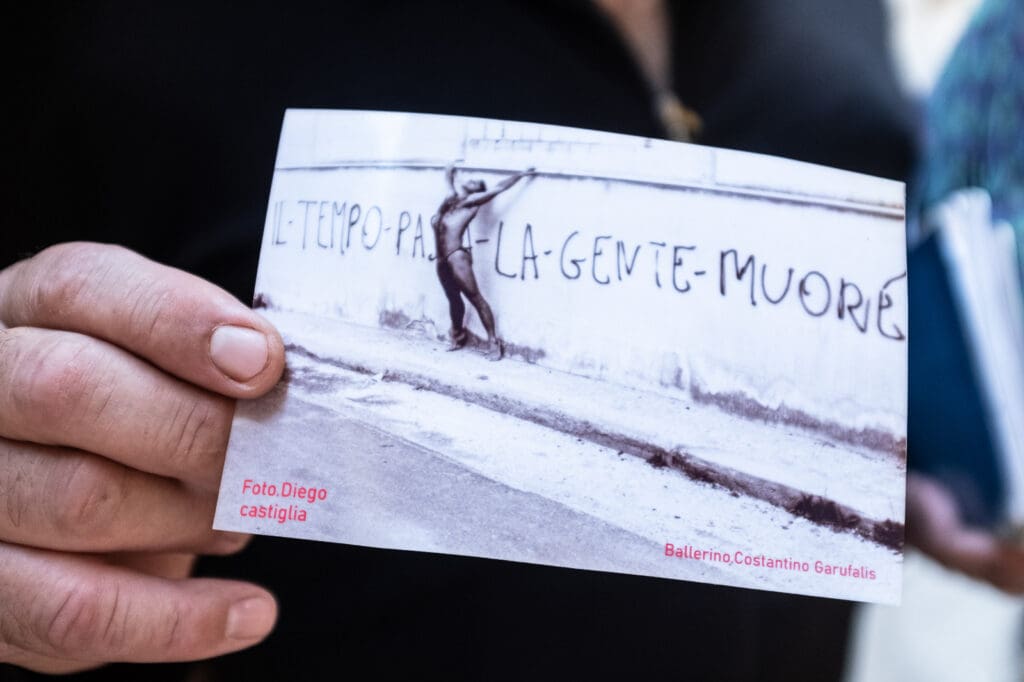

So begins the libretto of a tango opera entitled The Devil. I still keep three copies in three different languages: Italian, English and Greek. Constantine, the author of this booklet, hopes that someone reading it will make his dream come true: to see one of his plays performed on a theater stage.

Constantine is a dancer and actor originally from Patras. He has lived in Athens for over 30 years, and meeting him on Dionysiou Areopagitou, the pedestrian street surrounding the Acropolis, is not tricky.

Telling the story of Constantine is like observing the Greek capital from above. One must observe, set oneself to listen, and only then try to piece together the puzzle of two destinies, that of a very modern city that contains within itself the ancient, golden image with the still intact strength of a goddess, Athena, and that of a man with sunburned skin, a native of a land still vibrant with myths and legends.

“Do you remember when we met? You had just arrived in Athens. How many years have passed?” He squints his hazel eyes and looks at me. “Five, we met five years ago.” His Italian is perfect. Constantine lived in Italy for a long time as a very young man. He was just 20 years old when, a ballet dancer, he moved first to Bari and then to Turin. The physique is massive but still retains the imprint of a certain grace in the movements. Then again, dancing is still part of his life, although not as much as it used to be.

A regular appointment

When I return to Athens, very often by now, it is a fixture for me: to see Constantine again and to listen to his stories.

On a very hot and bright November day as if summer had decided that the time to leave this land of the gods had not yet come, we meet at the usual place, near the Areopagus Hill, one of the city’s hills located between the Agora and the Acropolis. According to legend, right here, on this high ground where tourists and Athenians now admire the Acropolis from the other, the god Ares was allegedly accused of murder and tried for the killing of Alirrotius, the mythical son of Poseidon and the nymph Eurythys.

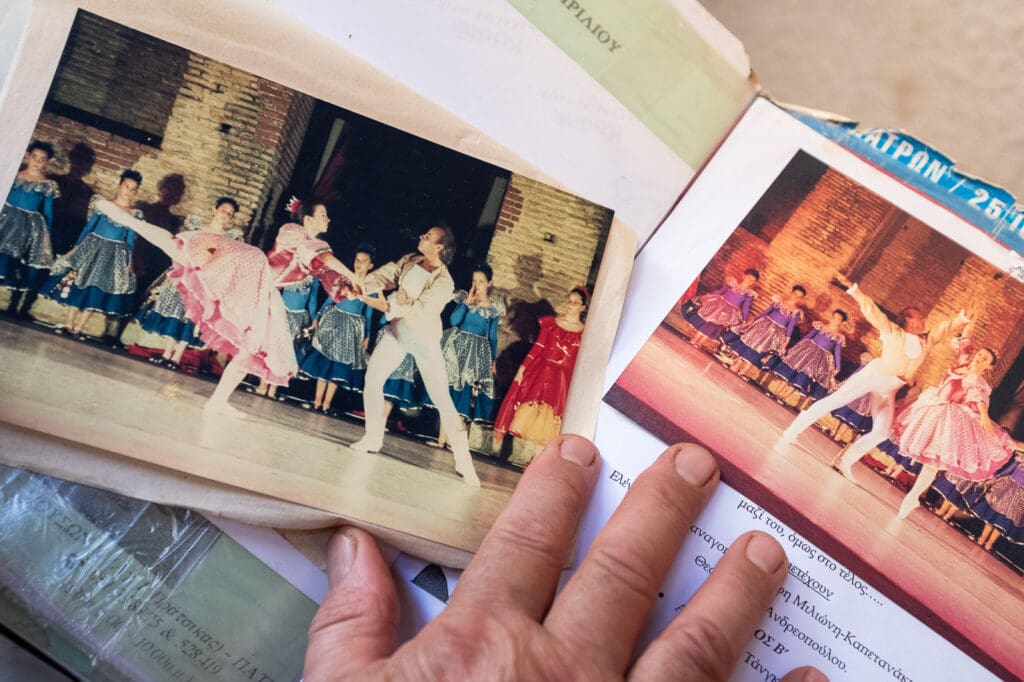

Constantine has his backpack with him, and I am not surprised that it contains some of the many newspaper clippings and photographs from his shows around Italy, Greece, and France. Valuable memory material. Constantine proudly shows it to those who, like me, show interest in his life. Photographs scroll by of him as a young man in his 20s dancing on stage at the Teatro Regio in Turin and other famous theatres in Italy. “When I arrived in Bari, I didn’t speak Italian, but I had studied French, which helped me learn your language quickly,” my Greek friend smiles. He always smiles when he recalls his past, his gaze open on the photos carefully protected by a clear plastic bag. I still keep some photocopies of those newspaper clippings he gave me as a memento of one of the first times we met again on my frequent returns to Athens, a city home to me.

The freedom of those who do not give up

This time, in addition to our usual rendezvous near the Areopagus, I also decided to join him at his home in a neighbourhood south of Athens. He manages to live with very little, Constantine, in a very cramped space, wedged into a small, narrow, long building with a single floor hidden behind the facade of a white building. The light of these autumn days is too bright, bordering on cruel. Everything is too real, concrete, nothing can be hidden.

The house, far from the center of the city, near the sea, is very modest: a bed, a low table and a rope with clothes and what used to be his stage clothes, clothes he used in his theater, hanging on it. “Now, unfortunately, it no longer exists,” he tells me in a nostalgic tone, recalling that time, “the rent was too high, and I had to close my beautiful theatre.” Property rents in recent years have risen significantly in the Greek capital, partly due to gentrification. A boom in demand is primarily due to the city’s growing popularity as a tourist destination and the rise of short-term rental platforms such as Airbnb. As early as 2019, the year after I arrived in Athens, data from Pwc’s “Emerging Trends in Real Estate® in Europe” report marked Athens as the city most likely to experience significant rent increases. So it was. For many, but especially for those like Constantine, who do not have regular jobs, rent is a huge problem.

“I have a small house in Patras, but I don’t want to rent it; I need to feel free to return to my city whenever I want. All my memories are there. Besides, even if I wanted to rent it, I would have to renovate it first, and I can’t afford that. I would have to give it for cheap and it’s not worth it, I wouldn’t even pay taxes on it, ” he tells me looking into my eyes. The tone has thought long and hard about his situation, considering all possible options. “Besides, I love Athens. I don’t want to leave this city and my cats.”

A symbol of peace

When I visit him, we sit outside in front of the house’s front door. It is still hot, the sun is setting, and the walls of the narrow outdoor hallway where we stand are beginning to tinge an orangey yellow like the persimmon fruit my Athenian friend has just offered me. “Eat it, it’s so good. You know this is the fruit of the gods, right?” He says, winking at me. Diospyros kaki, “food of the gods.” Perhaps Constantine does not know that there is another nickname, more recent origin: “tree of peace.” After the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki in 1945, some persimmon trees were the only living things to survive. Since then, the persimmon has been the emblem of peaceful resistance and the allegory of those who fight every day against the atrocities of war by fighting tenaciously and without violence.

Dancing continues

For the past few months, Constantine has taught tango and Latin American dance at an association south of Athens. One evening I accompany him; I have never seen him dance, and I am curious.

I notice that when he teaches, his face lights up with a bright, different light; surely the same light that animated him when he was very young, when he danced on stages all over Europe. The window is open on this cloudless and still hot November night, so it almost seems like the stars have replaced the spotlight of a time long gone. In a room with yellow-orange walls reminiscent of the fruit of the gods, dancing continues in a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Athens.