People of migrants seeking their fortunes

The Toupouri are an ethnic community settled in northern Cameroon and southwestern Chad for more than 200 years, particularly in the Lake Chad basin. Today the Toupouri are one of the majority communities in Cameroon’s large agro-industrial towns. They reside mainly in the far north, in the Mayo Danay and Mayo Kani departments. It is estimated that the Toupouri make up more than 30 per cent of the country’s total population (28,000,000).

The Toupouri are a dynamic people of farmers and ranchers. However, the high population density, resource poverty, and hostility of this region of Cameroon force them to engage in perpetual migratory movements within the country.

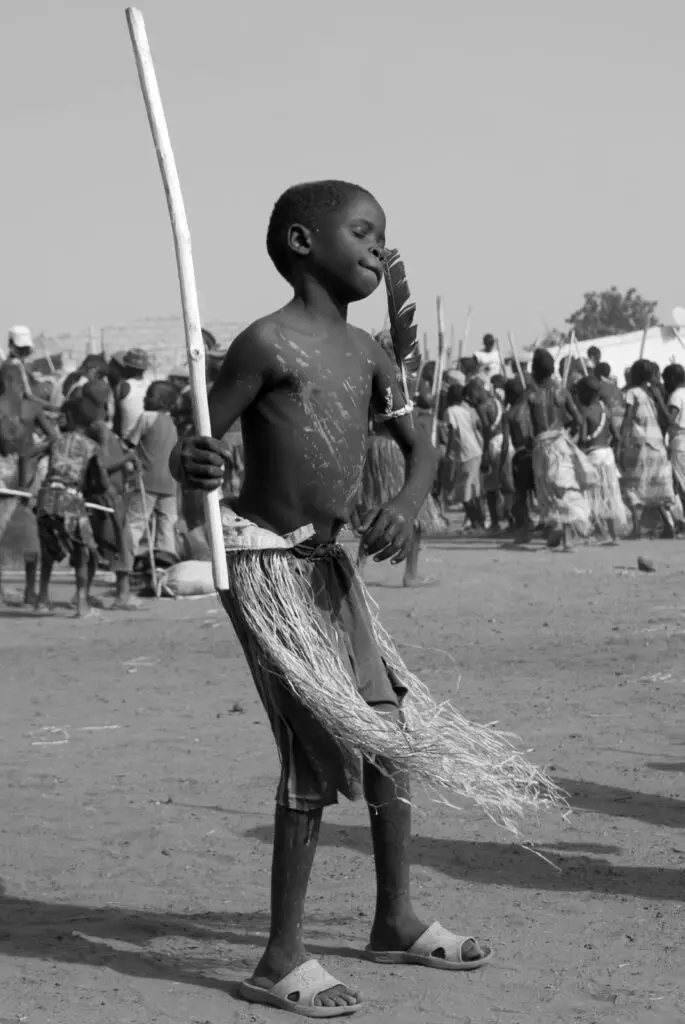

Les Toupouri et la Fête du Coq – ©Djilo Louis Blaise

Essence of community

FEOU KAKE is a time of thanksgiving offered annually to the gods by members of this ethnic group to thank them for the abundance of crops. It is practised by all the clans that make up the Toupouri community, scattered between Cameroon and Chad. The ceremony begins at the foot of Illi Hill (in the Fianga sub-prefecture), where the Toupouri supreme chief resides, and then involves all other communities.

This ceremony takes place once a year at the end of the rainy season. It lasts one week and marks the beginning of the new year. On this occasion, the WAN DORE(supreme leader of this ethnic group) sacrifices a rooster to the PANKAKE(father of the rooster) so that the next harvest will also be good and thus ensure the prosperity of the community.

Traditionally, the ceremony ends with WAIWA, a dance that for hours involves all members of the Toupouri community. To the frantic rhythm of drums, animated by vigorous drummers, the Toupouri dancers-who use to dress eccentrically on this occasion-dance for hours, drinking BIL BIL, a local beer made from sorghum.

NOTES ON REPORTAGE

At the invitation of the Regional Delegate for Culture in Northern Cameroon, in December 2014 I went to the Ouro Labbo market to witness the Waïwa dance marking the end of the Rooster Festival ceremony celebrated by the Toupouri community in the town of Garoua.

Arriving at the site of the ceremony in the early afternoon, I was dazed by the scent of the hot, dry ochre powder that dominated the atmosphere. After introducing myself to the festival manager, I sat on one of the many chairs set up for the occasion and watched the participants and spectators arrive in the large square where the ceremony then took place.

The ceremony began two hours later, with the rumbling of drums played by a group of four percussionists, which was followed by other groups scattered around the square. At the same time, dancers began to perform slow, rhythmic steps, raising clouds of dust. I took the opportunity to mingle with the crowd and take these photos. Initially, it was not easy: I had to face the questions and puzzled looks of some people surprised to see me on that stage.

My wait-and-see attitude and the various explanations given to those who came to meet me allowed me to blend in, even creating enthusiasm among the protagonists who, in turn, asked me to catch them in their various poses. After five hours, arriving at dusk, I left the ceremony.